Political Rhetoric in Divisive Times: Lincoln and Churchill

Share

By Hillsdale College August 9, 2019

[MUSIC PLAYING]

HUGH HEWITT: Morning glory, America. Bonjour, hi, Canada. Greetings to everyone listening across the globe via HughHewitt.com, or via Townhall TV, if you’re watching at TownhallTV.com. You can also watch the cameras in the studio at HughHewitt.com.

It is the last radio hour of the week, the 15th hour of radio that I’m doing this week—hosting. And it’s always the Hillsdale Dialogue. It’s when I go big picture with Dr. Larry Arnn, president of Hillsdale College, or one of his colleagues. All things Hillsdale are collected at Hillsdale.edu. All their online courses, you can subscribe for free to Imprimis. You can get all of the Hillsdale Dialogues that I’ve conducted with Larry Arnn from 2013 to the present, or with Matt Spalding, or any other great faculty. They’re all collected at HughForHillsdale.com for binge-listening.

But I know what I want to get done today, and I want to get it done for the benefit of the country. Dr. Arnn, how are you this morning?

LARRY ARNN: Very well, how are you?

HEWITT: I’m good, but I am challenged by a week in which the rhetoric in America fell off the edge. We had terrible massacres in El Paso and Dayton. In our old, friendly Orange County confines, a man went on a rampage and stabbed four people to death. It’s been a crazy week, and the response of the political left is—by Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Kristin Gillibrand, Beto O’Rourke, and Pete Buttigieg—to call the president of the United States a white supremacist. What do you make of that?

ARNN: Well, so I’ve been reading the rhetoric of the Civil War this morning, you know, and I mean the lead-up to it—during the war, too. And you don’t find anything like that from the leading people. Lincoln was very tough. And, when he was a young man, he was sued for slander and libel several times, and he was once challenged to a duel that he almost fought. But he matured, and he didn’t do that after that.

So, if you read the Lincoln-Douglas debates, which we have read on this show, they’re very tough, and they’re brilliant, right? But they’re not personally vindictive.

HEWITT: That’s it. That’s it.

ARNN: And now, you do get that. I forget the name of the man who did it, but Charles Sumner, Massachusetts senator, was beaten half to death on—

HEWITT: South Carolina congressman. Yeah, South Carolina congressman. Pickering, right? [Preston Brooks]

ARNN: And that was a—[LAUGHS] that was a civil piece of violence, because it was thought to be a matter of honor. Anyway, things like that happen, and there were crazy guys—that were people—the rhetoric was violent about secession in many of the Southern states, but not the leading people. And they were leading people in part because they matured to a place where they sounded like people who might be leaders of a nation.

But, I mean, Donald Trump—the idea that he’s a white supremacist—that’s crazy. And there’s no evidence for that whatsoever.

HEWITT: That is crazy, unless you define white supremacy into people you don’t like who happen to be white. That’s what is going on.

ARNN: That’s right. And it’s hard to make an argument. Another thing about it that’s bad is—if you listen to the Lincoln-Douglas debates, they invite you to think. What’s exposed between the two of them is that this is a very hard problem, and we have to face some things. One thing we have to face is, most of us don’t—most of us voters, most of us white people—don’t want a lot of black people around. And that’s one reason why this is so complicated.

And Lincoln did not go so far as to say, I favor the social and political equality of the black. He denied that he favored that. But then he—and if he hadn’t denied that, he couldn’t have won. One of my teachers used to say they would hold the conventions of the Republican Party on telephone booth.

Well what did he say? He said, I don’t understand if you think that the black woman—he used her—is your inferior, why do you get to own her? Why don’t you just let her alone? And doesn’t she have the same right we have to eat the bread that she earns with the sweat of her own face?

So that’s elevated and beautiful. And Douglas, in my opinion, never ascends to that level. He’s got lower arguments to make.

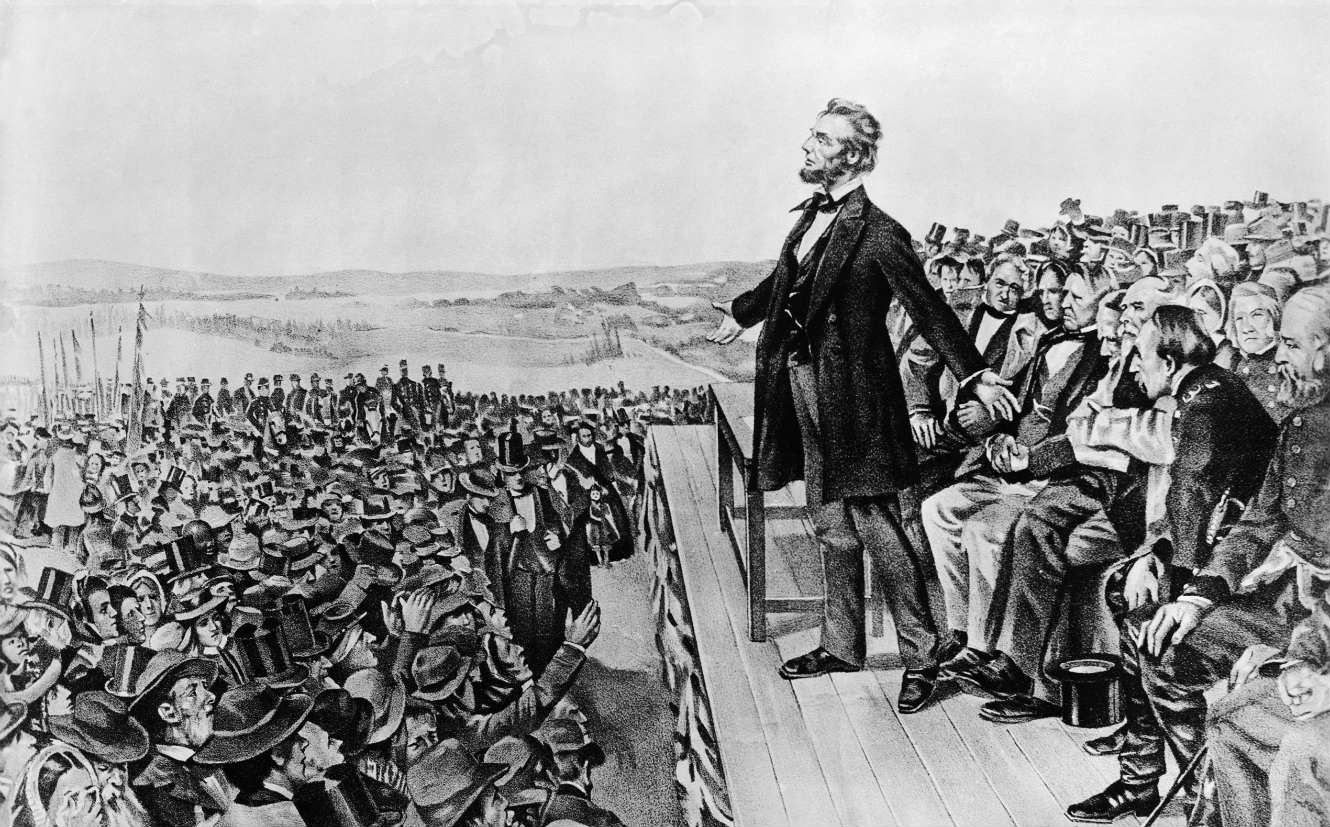

HEWITT: I said a prominent Republican this week linked to the Cooper Union speech, because I said, this is how people need to respond. You have to make an argument. And would you tell people a little bit about what Lincoln did in that speech and why it made him a superstar overnight?

ARNN: Well, it’s one of his speeches that’s—the reaction to it is best recorded. So Lincoln wins the popular vote in the 1858 Republican statewide election for Senate. And they gain seats in the Illinois Senate—the state senate—which is, back in those days, the one to pick the senators. They gain seats, but they didn’t get a majority. And so the Democrats had a majority, and Douglas was reelected senator.

But it was a noble effort. And Illinois, out on the frontier, was, back then, a swing state. And so that made Lincoln important, right? And so the bigwigs in the party were back in New York and Ohio, and those were settled—New York was original, and Ohio was settled much earlier than Illinois.

And so this guy out on the frontier, his name got in the papers in the East, and then he went back east and he made a series of speeches. And they’re very beautiful speeches. And there’s an account of the Cooper Union address, which is an old institution still standing in Manhattan in New York City. And he just galvanized the people. One of the descriptions goes like this. And we get into what Lincoln said in the argument in a minute.

But he said that—he began speaking, and he was just standing erect with his arms by his side. And then he didn’t move about. Stood on a stage—of course, no microphone back then. And that he had a high voice. And at first, it sounded disappointing. And then the man describes that, as he talked, his body began to move slightly—never to walk around or change his position—his place on the stage.

And he began to move and just a little bit, and then his hands began to come up. And they were—they didn’t gesture much, but he was sort of holding both of his hands up eventually above his waist. And he would sort of move with his points, sort of bow a little bit. His hands would bow.

And by the end, his hands were up quite high—not above his head, but quite high. And his points were being made like a conductor. And the newspaper man who wrote about the speech said that the audience sat in astonished silence for a minute after he finished.

HEWITT: Astonished silence?

ARNN: Yeah. It’s just that Lincoln was very effective, and he had a beautiful soul, and he could speak what it was thinking. And so it just really moved people.

One of my favorite things—there’s actually a book that I’ve kept open on my desk to a certain page since it was published in 1978. It’s called The Face of Lincoln. And this was given a few days after—so what The Face of Lincoln is, is a reproduction of every photograph there is of Abraham Lincoln. It’s a big, glossy picture book, coffee table book. Quite large, too.

And every picture is reproduced and painfully restored, so the pictures are really striking and large. And then, on the opposite page, there’s something Lincoln said or did at the time. So you can page through it, and one thing—you can watch the war grow on Abraham Lincoln’s face as he went through it.

But this particular thing is a few days after the Cooper Union address, and he’s in Hartford, Connecticut. And the next morning he gets on a train, and a preacher/journalist says, Are you riding on this train, Mr. Lincoln? He says, I am. And he said, May I ride with you? And Lincoln said, sure. And he asked him a question, and the question was, effectively, How did you write that speech?

Now I’ll tell you what he said in the speech. See, the Republican Party was formed around an attempt to fight slavery by constitutional means. The Constitution doesn’t give—didn’t give the federal government power to interfere with slavery in the states where it existed. And so—

HEWITT: One minute to the break. Go ahead.

ARNN: So the plan was to forbid it from growing into the federal territories. And that would place it in the course of ultimate extinction, and that would preserve both the Constitution and the Declaration. Well, I’ll tell what Lincoln said about this, but the puzzle or the confrontation he has about that is, if slavery is bad in the territories, why not abolish it in the states? And, if slavery is OK in the states, why not let it go into the territories? You are inconsistent, O Republicans.

HEWITT: So he grabs the—I mean, he goes to the heart of the argument, right?

ARNN: That’s right.

HEWITT: When we come back, we’ll talk about how Lincoln did that. It is a lesson for these times both on how to argue and how not to argue. Dr. Larry Arnn is the president of Hillsdale College. All things Hillsdale at Hillsdale.edu. Rhetoric and incendiary times is the conversation we are having. Don’t miss any of it here on The Hugh Hewitt Show.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Welcome back, America. It’s Hugh Hewitt. The Hillsdale Dialogue is under way, the last radio hour of the week with Dr. Larry Arnn of Hillsdale College. I’m Hugh Hewitt in the ReliefFactor.com Studio. When we went to break, Dr. Arnn—we’re talking about rhetoric and incendiary times—had begun to set up the Cooper Union speech by Lincoln by outlining the dilemma the Republicans faced, which was a charge of hypocrisy. If slavery was wrong in the territories, why wasn’t it wrong in the states? And if it was OK in the states, why wouldn’t it be OK in the territories?

So how did that Rubik’s Cube get unwound by Lincoln?

ARNN: So I’m going to describe quickly two different speeches given six days apart. I need them both because it’s in response to the Hartford speech six days later that Lincoln explained how he learned to think. So, in the Cooper Union address, he just asked the question—just like a really great teacher in a classroom—how do we know what the people who wrote the Constitution and signed it thought about slavery?

And he proceeds by taking the evidence—you know, there are 39 of them. And then he cites—it’s very orderly, and it’s one of those Lincoln arguments that builds to an ineluctable conclusion. And what he says is a lot of them later supported anti-slavery resolutions, and a lot of them advocated the end of slavery. And what he gets to is that nearly all of them, North and South, were vocal opponents of slavery for most of their life.

And so, if the question is, What were the people thinking when they wrote the Constitution?—then we know the answer to that. And it’s just a proof, right?

HEWITT: Yes.

ARNN: Remember, when you do that, when you come and make an argument based on evidence and reason, then you’re inviting people to answer you and discuss with you. And, when you call somebody a white supremacist, then you’re condemning him and writing him out of the political system.

And so, Lincoln doesn’t do that, right? The Confederate States and their governments seceded from the Union of the United States. He walked softly—spoke softly—when he was talking about them. He wanted to invite them back. In the Hartford speech, that’s where he answers the one about this paradox, this seeming contradiction that he wants to stop slavery completely in the federal territories, which, remember, listeners, was most of the Union.

HEWITT: Right.

ARNN: Bigger than the states. And leave it alone in the states. And so in the Cooper Union, he says—in the Hartford speech he says, If I see a rattlesnake, what I do depends on where it is. If it’s out in the garden, I’ll get a stick and kill it for fear that it will bite my children. But what if it’s in the bed with my children? I might not stir it up, because, if I stir it up, then it might bite the children, whereas it might just lie there or even crawl away.

And so this preacher/journalist thought that this was brilliant and said, How did you write it? And here’s what Lincoln said. This is how, by the way, you prepare yourself not to just be a name-caller. Elizabeth Warren is a highly educated woman. I don’t think she’s been studying the right stuff in the right spirit.

Lincoln says, Well, I was reading law, he says. And I kept running across the word demonstrate. (Every time that word appears in this article, this newspaper article—this preacher/journalist wrote about it—it’s italicized. Lincoln had probably said it with emphasis—demonstrate.) And I began to think that was an extraordinary kind of proof.

And so I read my Blackstone, and I kept reading law. And I finally looked up and said, Lincoln, you’ll never make a lawyer if you don’t learn how to do that. And so I left my position in Springfield and went home to my father’s house, and I did not return to work until I could repeat from memory all of the propositions of Euclid in his six volumes.

HEWITT: Wow.

ARNN: He went to learn. The reason I keep it onto my desk is that I read it to young people. Like my Federalist Society chapter last year—they wanted to start a journal. They’re really great kids, I had several them in class at the time. And they wanted to start a journal, and they wanted a speaker series. And I said—I didn’t like it. And so they found out, and they came to my office. We understand you’re concerned, and I said, I’m not concerned at all. And they said, why not? And I said, Well you’re not going to do that.

[LAUGHTER]

And I’ll tell you why not in a minute.

HEWITT: After.

[LAUGHTER]

Don’t go anywhere, America. The Hillsdale Dialogue with Dr. Larry Arnn. All things Hillsdale at Hillsdale.edu—not this conversation, but I wish we recorded it. Stay tuned, America. It’s The Hugh Hewitt Show.

Welcome back, America, it’s Hugh Hewitt. The last radio hour of the week means The Hillsdale Dialogue is underway. All things Hillsdale from Hillsdale College, the Lantern of the North, is at Hillsdale.edu. All of these conversations dating back to 2013—the last radio hour of the week—there are hundreds of them now—are collected at HughForHillsdale.com. This week we are talking about rhetoric and incendiary times, and we left off with the Federalist Society approaching Dr. Arnn with a list of wants, needs, and desires. And you spurned them.

ARNN: Well, Abigail—I won’t say her last name—the president at that time—she just graduated—she said, why not? And I said, well, Abigail, in ten minutes you’re not going to want to. And I read them that speech. And I read that from that newspaper article about Lincoln. And I looked up, and they got it in a minute, and their backs were stiffening up, they were straightening up and getting their chins up while I was reading because it’s very beautiful, this thing.

And I said, you wouldn’t want to leave the impression that people are insufficiently ambitious, would you?

[LAUGHTER]

HEWITT: And so they went away and they didn’t get their—they didn’t get their program.

ARNN: And see, that’s the point, right? I mean, we got a bunch of kids agitating for the convention of the states, they call it, which I think is a misnomer. And I’m happy to debate that. I don’t like the agitation. I’m going to tone it down, because they’re here to study and learn. And making these hard commitments when you’re 19 years old, and you can’t properly define the word politics yet or the word good or anything—you’re supposed to be learning to do that, just like Lincoln did.

And think what a reverence and humility it is to take the trouble to get it right. And the people who really do that—Lincoln and Churchill, for example—they have the ability to escape.

HEWITT: Do you know—I have to tell you, in contrast, Lincoln’s approach—I have seen a documentary this week called Remember My Name about the musician David Crosby, one of the great musicians of the ‘60s and ‘70s and also an addict many times close to death. His life is a wreck. He has no friends left. He’s 76 years old. He’s going to die, and he’s talking to Cameron Crowe about this life and how the music mattered.

Music is different from argument. Music is all emotion, and it’s beautiful. But it is a generation steeped in emotion and music, not really brought up on argument, Larry. So I’m not really surprised that—outside of Hillsdale graduates and a few other places—that we find many people trying to make an argument about why we have mass slaughters in El Paso and Dayton and what to do about it, but instead reverting to incendiary rhetoric. That’s what happens when you lose the ability to argue.

ARNN: Yeah. Well, the classic teaching about music—first of all, it’s one of the two modes of education in Plato’s Republic—music and gymnastics—training the soul and training the body. And music means both literally music, but also other things you read, and learn, and—one hopes—memorize that shape your soul. And good music—in Plato’s Republic and in Aristotle’s Poetics—good music is orderly.

And the reason you love Mozart is that—it’s a wonderful thing. If you just listen carefully, some works are very complex, and mere cretins like you and me, Hugh, can’t delve into the depths of it. But, when you listen to music, if it’s good music, then you anticipate what’s coming next. It’s like reading a book. And it teaches you the order of things. And, of course, that kind of music can raise the most profound emotion, but it is ordered.

I went to a lecture one time, and this music professor and a physicist from Stanford, if I remember right, were talking about music. And there were, like, 400 people at this thing. And they said, How many of you can read music? And a few hands went up. And he said, You’re wrong. You all can.

And then he started playing recordings of music, and he said, Hold up your hand when the note doesn’t fit. And you could hear it every time. If you’re listening to Schoenberg or something modern, you might not be able to tell. But every hand goes up. And he said, See? That’s why you like music. You can anticipate the pattern of it. And then, when it surprises you, that introduces a new order.

Well, all this stuff that’s going on in our country, we’re just not doing a very good job with our young people.

HEWITT: Boy, are we not. Now, I want to make sure we don’t run out of time, because incendiary rhetoric—you are also a scholar, not only of the Framing and of Lincoln, but of Churchill. And Churchill was a rhetorician, and on two occasions in the ‘30s, he had to often confront genuine white supremacy, right? He had to deal with the real deal.

How did he do so while maintaining the attention in the House, or did he give up on maintaining the attention in the House, in order to make his points?

ARNN: Well remember, Hugh, that Hitler—you and I wouldn’t be in it, right? Because we’re not Aryans.

HEWITT: We would not. I’m Irish, so we don’t count, yeah.

ARNN: Yeah, I’d be Jewish blood. Anyway, yeah, Churchill—and since I’ve made that point about music—really great political speeches, including the really hard ones, have that order in them that leads somewhere. That’s one of the main points of Aristotle’s Rhetoric. He regards the purpose of rhetoric as persuasion, he says, and you get lost in that because that’s the first thing. But then you find out later that, he says, it is a truth-disclosing capacity of public speech.

So here’s the strongest thing Churchill said about the Labour Party, and he stated it at a 1945 election where they wiped the floor with him. And, before I read it to you, I will tell you that Clement Attlee—and Churchill and Attlee were friends. They respected each other for good reason. Attlee was a war hero—had said the same thing about Churchill earlier, but nobody made a stink about that, right? The press then was kind of like the press now.

Here’s what he said: “No socialist government conducting the entire life and industry of the country could afford to allow free, sharp, or violently worded expressions of public discontent. They would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo.” Think of saying that in 1945.

HEWITT: When we know—when it’s real, when it’s across the Channel.

ARNN: “No doubt very humanely directed in the first instance.” You see? In other words, he’s not accusing them of being Nazis. They’re adopting arguments that lead that way. And that places the focus on the arguments and invites people to think about them. “It would,” he goes on to say, “stop criticism as it reared its head, and it would gather all the power of the supreme party and the party leaders. And where would be the simple, ordinary folk—the common people, as they like to call them in America—where would they be once this mighty organism had got them in its grip?”

So, see, that’s a strong thing to say. They would have to fall back—and he doesn’t say, They want a Gestapo. He actually says, They do not want it. He doesn’t say, They are Nazis. He says they’re not Nazis. He says that what they’re advocating will lead that way. And see, that’s something different than a condemnation. That’s an appeal to reason with me about this. Don’t go that way.

HEWITT: What was the reaction to this speech, though? What was the reaction to the famed Gestapo speech?

ARNN: Well, it’s a little mixed, but it’s referred to as “the crazy speech” now by historians. And he lost the election big time. Was that the reason he lost it? Well, I don’t think so—for one reason, because Churchill was immensely popular all through the war, and, during the election, he got his largest majority he ever got in the 1945 election in his personal constituency.

So he was the greatest man in the world, but you don’t vote for the prime minister unless you happen to live in Woodford, which was his constituency, one of 650. You vote for your MP of one party or the other. And the Conservative Party had been in charge for a long time, since 1935, and they led the country into and through that war that was crippling. And they were responsible for it.

HEWITT: Because they had not stopped it from occurring despite Churchill’s warnings that it was coming.

ARNN: That’s right. That’s right. And they had the power. Now, you wouldn’t fairly pick the Labour Party over the Conservative Party at that time, because the Labour Party was at least as bad. But never mind, they were responsible, right? And then the war itself, you have to understand the amazing reach of that war, because Britain—they were borrowing money by the end of the war to be able to buy enough food to feed their people. And they had rationing until a year after Germany got rid of it, and they just mortgaged their whole future.

And Victor Hanson writes in his book a really wonderful passage about how effective the British war effort was, how they got the last ounce out of themselves. And so that one thing by Churchill—I don’t think it’s the reason he lost the election, but it certainly didn’t win it for him.

HEWITT: When we—

ARNN: Those other facts were bigger.

HEWITT: When we come back, we’re going to talk about the incendiary rhetoric of this week, and going forward, and whether or not they are of more Cooper Union, or the “crazy speech,” or something entirely different, which is an abandonment of argument. That’s what I think. We’ll hear what Dr. Larry Arnn thinks after the break. Don’t go anywhere, America. I’m talking with Dr. Larry Arnn, president of Hillsdale College. All things Hillsdale are at Hillsdale.edu.

Over at HughHewitt.com, there is a banner. Dr. Arnn and I are agreed that the government of Venezuela is a police state, an authoritarian, totalitarian evil state. We are agreed that the Cubans who are executing Maduro’s people—7,000 extrajudicial killings—are genuinely gestapo. They are the real deal. And, as a result, millions of people have fled, hundreds of thousands of them are in Colombia, and they are starving.

And Food for the Poor has gone down there to feed them, and I am helping Food for the Poor feed them. And the fetching Mrs. Hewitt and I dug deep at the beginning of this week, and I’m asking you to do the same thing and to make a donation for Food for the Poor right now as the weekend begins. At the Crisis in Latin America, it will go right down to Venezuela—to Colombia, not to Venezuela. The aid cannot get into Venezuela.

These people do not want to come to America. These people are displaced from Venezuela. They want to go back to Venezuela, but in the meantime, they are starving. And, if you want to help them, call 855-359-4673. That’s 855-359-HOPE. John Bolton is on the front line here, President Trump is on the front line here, and you can be on the front line here. You can help these people. $100 provides 2,500 meals. The banner is Crisis in Latin America. It’s at the top of HughHewitt.com. Please be generous, the need is urgent. Maduro is such a criminal.

I’ll be right back with Dr. Larry Arnn on The Hillsdale Dialogue as we continue the conversation about “Have we gone over the edge rhetorically in the United States?” I think we did this week. I don’t know if we get back up over the cliff. I’ll ask Dr. Arnn after this. Stay tuned.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Welcome back, America, it’s Hugh Hewitt. The Hillsdale Dialogue is wrapping up for this week with Dr. Larry Arnn, president of Hillsdale College. It is the Hillsdale Dialogue. We do this every week in the last radio hour. All things Hillsdale—their online courses are amazing. The Imprimis newsletter is free. You just have to go to Hillsdale.edu. When Dr. Arnn comes to a city or town near you, and you hear about it, go hear him give the talk about the Framing and education in civic America.

So, Dr. Arnn, now we’ve talked about incendiary rhetoric, I’d like to ask what your advice to President Trump would be about responding to rhetorical excess accusing him of white supremacy—as you said, basically reading him and those who support him out of politics—because you and I agree that white supremacists are evil and ought not to be encouraged or tolerated.

ARNN: That’s right. And yeah, so, first of all, I think Trump’s rhetoric is generally pretty good and getting better and sometimes great. So I looked through the things he said in the wake of all this, and he’s learning while he goes. He didn’t, in my opinion, give a bad message about Charlottesville a couple of years ago. He didn’t get it quite right the first time.

And so he’s getting it right now. And there’s an opening. I think his message needs to swell. And we’ve seen the tough, I-can-take-anybody-on Trump. That’s how he got—that’s how he won the primary. And we see more of, and we need to see a lot more of in the next election, the man whose rhetoric rises to the sublime, and that’s very hard to do, of course. I happen to know some of the people who helped him with that, and they’re not far off being able to do it. And he’s very good himself.

But you want to—because isn’t the opportunity ripe for somebody to make a powerful argument that comprehends all of this and shows a way out of it that can bring us all together?

HEWITT: Yeah, and in fact—

ARNN: And that’s what Lincoln was able to do.

HEWITT: That’s what I did in The Washington Post. It will appear today. Each week, ten pundits write the Democrats. And I said, they all missed this week. There was an opening as large as possible to rise above, step up, and instead, they all stepped into it. And they did not do what Bobby Kennedy did on the night of the assassination of Martin Luther King, which is to appeal to reason and unity in a high—in a beautiful way, quoting Aeschylus about the grace of sorrow.

And none of them did that. Not one of them reached for unity, Larry Arnn.

ARNN: Yeah, isn’t that funny? And as I say, I think there’s an opportunity there, right? And it’s irresponsible, I think—and I don’t accuse either party of this alone. I think that the primary system drives candidates to the extremes. It’s irresponsible to take positions now that will get you the vast majority of the radicals who dominate Democratic primaries, at least in the funding and in the activism, and not think about all of America. Our much-admired Kim Strassel this morning writes an article about what they’re saying about gun control, and they’re just vying with each other to say who can confiscate the most guns.

And 48% of the men in America are gun owners, and vast majorities of them say they can’t do without it. And very large numbers of women—I can’t remember from her articles—in the article this morning—also own them. And so—I’m going to come take your thing, right? And that’s not good, and it doesn’t lead us back toward figuring all this out.

HEWITT: No, it doesn’t, and that is—I don’t think it’s a matter of despair. I think it will burn out. I don’t think we reward that politically. And, if we do, we’re in a bad place.

ARNN: Yeah. There are forces in America, left and right—I think mostly left, but I’m not sure—and they are extreme. And they do seem to have more—exercise more authority now, at least in one party.

HEWITT: Well, the mob showing up on Mitch McConnell’s lawn with a voodoo doll and calling for his death—this is not normal in American politics, and it is not being condemned widely or rapidly. Last minute to you. I think that is a bad sign.

ARNN: Yeah, well, there’s nothing more urgent right now than to study the best examples of the past and try to emulate them, because they are there. And they, too, did not—the best of them did not invent what they did. They studied and learned.

HEWITT: They got their Euclid.

ARNN: Yeah, study your Euclid.

[LAUGHTER]

HEWITT: You know what? I’m not going to go off and do that, but I’m impressed by the example. I’ll do the best I can. I’m listening to Andrew Robert’s book on Napoleon. That’s pretty doggone good, but that’s not Euclid.

ARNN: Yeah.

HEWITT: Dr. Larry Arnn, always a pleasure. This Hillsdale Dialogue and all of them will be collected and put up at HughHewitt.com, also available at Hillsdale.edu. Go over and get Imprimis. Get yourself to the library. Get yourselves to the higher thing. Get yourself away from the television, and have a great weekend. I’ll be back. You’ll see me on Meet the Press on Sunday. I’ll be back right here on Monday morning on the next Hugh Hewitt Show.

[MUSIC PLAYING]