The Electoral College

Share

By Hillsdale College March 22, 2019

HUGH HEWITT: Morning glory, America. Bonjour, hi, Canada. Greetings to the rest of the globe from the ReliefFactor.com Studio. I am Hugh Hewitt on the West Coast, headed to Ohio later in the day—blessedly will not have to stop in Michigan today, where we find our morning guest, Professor Adam Carrington of Hillsdale College. He is the Hillsdale Dialogue participant today, and he's up in Hillsdale. He teaches so much, it makes me tired looking at this.

He teaches Politics 101: the U.S. Constitution; Politics 301: American Government; Politics 303: The American Presidency; Politics 305: Civil Rights; Politics 306: Political Parties and Election; Politics 412 and 504: Politics and Literature; Politics 416: Montesquieu; Politics 742: The American Presidency; Con Law and Con Law II; Hamilton: the Man and the Musical; Politics in the Bible. Honestly, Adam Carrington, you're giving me a bad name. I teach two classes a year.

ADAM CARRINGTON: Well, I would say that President Arnn would still say he doesn't get his money's worth out of me.

HEWITT: Well, of course, he would. That's a given. But we know that he does. I'm just curious as to how you do that many course preps. We're going to dive into the subject matter, many of them today. But is it like a manic thing with you?

CARRINGTON: Well, I mentioned that I do the Hamilton, the Man; the Musical—is a one-credit-hour course here. I guess I write like I'm running out of time.

HEWITT: Oh, we use that song. That's a bump song for us.

CARRINGTON: Yeah.

HEWITT: That's it, you write like you're running out of time. How long have you been at Hillsdale?

CARRINGTON: This is my fifth year. I'm about to complete my fifth year.

HEWITT: And you went there right out of Baylor, where your PhD is from?

CARRINGTON: I did.

HEWITT: All right. So it's great to have you on. I appreciate your joining me again. Everything Hillsdale is collected at Hillsdale.edu—everything, including great courses on the Constitution. All of the Hillsdale Dialogues, going back to 2013, are collected at Hugh for Hillsdale. Go there, get smart, but we're going to talk about this: two articles, Professor Carrington.

Kevin Williamson has an article with National Review today that is called “The ‘Burn It Down!’ Democrats” and begins, “The Senate. The Electoral College. The First Amendment. The Second Amendment. The Supreme Court. Is there a part of our constitutional order that the Democrats have not pledged to destroy?”

At the same time, over at The New York Times, there is a column by Jamelle Bouie, “Getting Rid of the Electoral College Isn't Just about Trump: But Does Anyone Really Think Popular Vote Losers Make Better Presidents?” Are you astonished, as I am, that this has become the central debate in the Democratic primary?

CARRINGTON: I am surprised that they would make this the focus, given that there are other things that I think could be much more effective for them. I mean, they're not asking my advice, but to go after the constitutional mechanism of selecting the president, especially right after it's the reason they lost—it looks like sore loser-ism.

I respect it a lot more. There's an article I sometimes get my students from The New York Times in late 2008 saying, OK, President Obama won. And we're still opposed to the Electoral College. But, right now, I think it just shows a bit of out-of-touch-ness and a bit of lack of self-awareness.

HEWITT: Now, one of the arguments Kevin makes is not out-of-touch-ness and unawareness, but stupidity, meaning they have been taught that anything democratic is good, and anything non-democratic is bad, and that civics, and maybe history, and maybe some idea of what happens with pure democracy has vanished from our curriculum. What do you think?

CARRINGTON: Absolutely. I'm teaching The Federalist Papers for the first time right now—to add to the whole list of courses, by the way. And the thing that they over and over say is that the history of republics—the history of popular governments up to that point—is actually really bad. In other words, republics that have not been aware of their own weaknesses have collapsed, and collapsed so often, so violently, so horrifically that we've gotten to the point where some people are saying people can't have free government.

And what they say is, what you can't do is assume that republics are—that by making people a republic, you cure them of their bad human nature, their bad tendencies. And I think the brilliance of the constitutional system, and the Electoral College included, is it is a republic that is aware of its own weaknesses and, therefore, doesn't look to purely be a republic.

It looks to channel, and move, and make the way that it makes its decisions still republican, but a way that fights off the problems of pure democracy. I think that is something that we're not paying attention to. You know, I heard someone once say, man learns from history that man doesn't learn from history.

HEWITT: Yeah.

CARRINGTON: So, this is, I think, a good example of that.

HEWITT: My short-form argument is that the Constitution preserves freedom, and that this country is built with the idea of maximizing individual liberty. It can't be complete, but it needs to be maximized. Generalissimo—who is our producer—Dr. Carrington, had a conversation with a young friend last night about this very subject. Generalissimo, tell Professor Carrington what that was.

GENERALISSIMO: So, this is a 15-year old who is trying to do an English project. He's got to come up with a subject that is a current event, political, and controversial. And he just needed some ideas. And I said, so what about the question of whether the popular vote is how we should select a president?

He goes, Oh, that's a really good one. So he starts thinking about it, and he says, I think we should, because the Electoral College was designed by the Founders to prevent a civil war. And it failed to do that, and it's clearly failing now. So, what's an answer that I can give a 15-year old that he'll understand?

CARRINGTON: I think a good answer would be that why—maybe a good way to put this would be, why sometimes do you and your parents say to not even go down the candy aisle in the grocery store? Why do you sometimes just avoid that altogether? It's because you might put yourself in a place to make a bad choice. You know, if you're on a diet or if you're doing something else.

And that the way the Electoral College sets things up is that it channels how we make choices so that we put ourselves in a position to make better ones. And, just like people on a diet or people in the grocery store avoid certain aisles, that's what I think the Constitution tries to do in how we set up our way of doing so.

HEWITT: To his specific argument, though, that the Electoral College was supposed to prevent the Civil War, my response is, no, it didn't. No, it wasn't. It was designed to represent small states against large states, and to keep factions in check, and to make sure that people— “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” But we are not. So I think his premise is wrong.

CARRINGTON: No, I think that's a good way to put it as well, that our—and I think what you said earlier is a good point to say—that, if you look at the Declaration of Independence, the first thing it says the government's job is, is actually not even to represent the will of the people. It's to protect and secure inalienable rights.

But part of that is recognizing the consent of the governed. But that means the consent of the governed must be channeled in such a way that it furthers liberty, that it furthers individual rights. So, what a lot of people say is—they make democracy too simplistic. They say, as long as the inputs, the process of going in, seems in some abstract way fair—you know, one person, one vote—that it's good, it's fine.

Whereas the Founders wisely were saying, no, no, no, no, we want to know what the output is going to be. What kind of majority is going to be created? What kind of person is going to get elected, normally? And unless you ask that question, you're not asking the right questions, as far as what kind of process is going to be most fair, just, and good for the American people.

HEWITT: Now, at Hillsdale, you self-select for smart kids who are interested in the constitutional order. Do they get the Electoral College, Professor Carrington?

CARRINGTON: They do. And there are always some who want the popular vote. And, to be honest, if you look at the convention notes, there were very prominent Founders that were in favor of a popular vote. But they decided in the long run that the Electoral College was satisfactory, and even, I think, some of them came to believe, better.

But, generally, I try to lay out a good argument for both sides. But, for the most part, I think they really do see that issue, that the Electoral College shows not just democracy but a thoughtful and intelligent democracy—aware of what it needs to do to have a good outcome. And I think that happens here.

HEWITT: And the Framers were very aware. I mean, they knew their Plutarch. Hamilton studied it by candlelight at Valley Forge. General McChrystal made a big point of telling me that when he was a guest on my program. They knew their history of what happens when you have direct democracy.

CARRINGTON: Absolutely. Read the beginning of Federalist 9, written by Hamilton, where—or read Federalist 10 with Madison, where he says the history of democracies has been—they have been “as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.”

And what that means is that you can have a tyrant of one, and you can have a tyrant of 51%, because human beings, as much as there is good in them, there's also the will to be tyrannical over others, the will to want to violate the rights of others.

And what we need is a government system that pushes against that while still recognizing the consent of the governed. And that's what I think the—again —the genius of the system is.

HEWITT: I'm coming right back with Professor Adam Carrington of Hillsdale College. This is the Hillsdale Dialogue, our weekly march down a big issue, a big piece of history, and a big piece of constitutional law. The Electoral College is on the table, since the Democrats have put it there. Don't go anywhere, America. It's The Hugh Hewitt Show.

AARON BURR: Alexander joins forces with James Madison and John Jay to write a series of essays defending the new United States Constitution, entitled The Federalist Papers. The plan was to write a total of 25 essays, the work divided evenly among the three men. In the end, they wrote 85 essays in the span of six months. John Jay got sick after writing five. James Madison wrote 29. Hamilton wrote the other 51.

How do you write like you're running out of time? Write day and night like you're running out of time. Every day you fight like you're running out of time, like you're running out of time. Are you running out of time?

HEWITT: Welcome back, America. It's Hugh Hewitt. That is from Hamilton. My guest, Professor Adam Carrington, in fact teaches a course on Hamilton: The Man and the Musical. I do love that song, don't you, Professor?

CARRINGTON: I do. I was very happy. Before the musical came out, I actually knew it was coming. And I played for my students, before a class, the performance Miranda gave at the White House. And I said, I really hope this is good. And I do think, as a political scientist, I can always quibble. But I think it's a great introduction to many Americans that might not otherwise be interested in the Founding, to get them started into it.

HEWITT: I saw it again this weekend, this past weekend. I saw it in San Francisco. Burr stole the show. We had an understudy for Hamilton, but Burr's role is very, very good. It's sort of the nemesis of everything that is American. Now, I want to go, though, to the strongest arguments. You made this point. If you're going to defeat arguments against the Electoral College, you need to defeat the best ones against the Electoral College, correct?

CARRINGTON: Right.

HEWITT: And James Boyle in the—Jamelle Bouie—I want to make sure I get his name correct, because I don't want it to be—Jamelle Bouie writes in The New York Times today that Madison himself was not worried about a president being directly elected. He was worried about states being underrepresented. He was worried about conflict.

But Madison “referred to ‘pure democracy’…he meant direct governance by the people. ‘A society consisting of a small’” numbers of person. “He contrasted that with a representative democracy, a ‘republican’ government. And while Madison agreed to an Electoral College, he also saw the merit of choosing a chief executive by popular election.

“‘The people at large,’ he argued during the Constitutional Convention, ‘would be as likely as any that could be devised to produce an Executive Magistrate of distinguished character. The people have generally could only know & vote for some citizen whose merits had rendered him an object of general attention and esteem.’” Was he wrong?

CARRINGTON: Was Madison wrong?

HEWITT: Yeah.

CARRINGTON: I think that this is an instance where, in some ways, you see the benefits of deliberating together and compromising, because Madison, Hamilton to a certain degree, James Wilson—actually, all of them did originally support a national popular vote. So I don't want to immediately just throw that idea out the window as wild and silly.

But I think, if you look at how Federalist 68 then defends the Electoral College, it shows that the system they came up with took the benefits of a national popular vote and then mixed it with a system that fights off some of the worries of it that come from the kind of direct democracy questions that even Madison himself had.

So I think that the national popular vote recognizes that we need consent of the governed. But I think it—what the Electoral College system itself does is channels that will in a way—makes candidates run in a certain way that, I think, is actually even better than what maybe some particular Founders originally preferred.

HEWITT: Now, I also want to raise with you a question—we only have a minute till the break. We'll come back to it in the longer segment—which is, by bringing up the Electoral College, Democrats are irresponsibly raising an expectation that it might actually go away. It will never go away, because the Constitution has to be amended by two-thirds of both Houses, or by a convention of the states.

And if two-thirds of the Houses send an amendment, it requires three quarters of the states. And there are not three-quarters of the states to abolish the Electoral College. Am I correct?

CARRINGTON: Yes. I think this is another classic case of over-promising that will result in under-delivering.

HEWITT: And is that bad for our republic?

CARRINGTON: Absolutely. If you start getting elected on what seem to be manifestly false pretenses, you're going to disappoint the people. That's going to undermine the relationship between officeholders and those that elect them. And that undermines the fundamental idea that republics are based, ultimately, on the consent of the governed.

HEWITT: We'll be right back—going to continue our conversation with Professor Adam Carrington of Hillsdale College. It is the Hillsdale Dialogue. All things Hillsdale collected at Hillsdale.edu. You can sign up for the free Imprimis speech digest, absolutely free, just by going to Hillsdale.edu. Go nowhere, America.

BURR: No one else was in the room where it happened, the room where it happened, the room where it happened. No one else was in the room where it happened, the room where it happened, the room where it happened. No one really knows how the game is played, the art of the trade, how the sausage gets made. We just assume that it happens, and no one else is in the room where it happened.

HEWITT: Welcome back, America. It's Hugh Hewitt. This is the room where the Hillsdale Dialogue happens, the studio. Joined now by Adam Carrington, a professor at Hillsdale College. Adam M. Carrington. You can follow him on Twitter, @Carringtonam, I believe, is his Twitter handle—A-M—@Carringtonam is his Twitter handle.

And, Adam, I want to go back to an article that came out this morning by our friend, David M. Drucker, at the Washington Examiner— “Republicans Resigned to Trump Losing 2020 Popular Vote but Confident about Electoral College.” It begins, “Senior Republicans are resigned to President Trump losing the popular vote in 2020, conceding the limits of the flamboyant incumbent's political appeal and revealing just how central the Electoral College has become to the party's White House prospects.” Is that good for the system?

CARRINGTON: I think, in the end, it's not good for that to be the norm. I think it is much better, as most of American history has been, for the popular vote winner to also be the Electoral College winner, because I think one thing the Electoral College does is it clarifies the majority, that winning the popular vote can sometimes seem closer than it appears, whereas an electoral vote majority can often be much more pronounced and therefore give a president a much more— sense of legitimacy.

But I think given that ultimately we are committed to consent of the governed, I don't think it's healthy for this to be the thing that always happens. I think the Electoral College has advantages—that I'm absolutely in support of keeping it. But I think it's better if they align with the popular vote most of the time.

HEWITT: Now, here is another paragraph from the Bouie piece in The New York Times: “Beyond issues of representation, there are other practical problems with the status quo. When margins between candidates are large, the Electoral College aligns with the national popular vote. But narrow margins throw it into chaos. The 1968 presidential election nearly went to the House of Representatives; in 1976, if you moved roughly 6,000 ballots from Jimmy Carter in Ohio and 18,000 in Wisconsin and Gerald Ford becomes president, despite losing by nearly 1.7 million.

“Indeed, the recurring prospect of a president elected with a minority of the vote inspired a major push to end the Electoral College beginning in the 1960s,” with an amendment introduced by Birch Bayh, who recently passed away, in fact, this week at the age of 91.

“In 1968, Bayh spoke before a committee of Congress.” It never got to the states, though. So, something—the inevitability of defeat, I think, is what stops us, or ought to stop us from having this conversation.

CARRINGTON: Absolutely. And I think something that I should probably say just a little more about is, what are these advantages that make our majorities more moderate with the Electoral College? And I think, in some ways—I think we're talking about the destabilizing effect. I think we need to talk about how the Electoral College stabilizes the electorate in a way that, if we were only doing the popular vote, it wouldn't. We'd always be talking about a couple thousand votes here, a couple thousand votes there, in a way that I don't think we do with the Electoral College.

What the Electoral College does is it forces candidates to create a national majority—that you can't just run up the vote totals in urban areas or suburban areas or rural areas. You can't just run up votes in the coast or the heartland. You've got to actually run across the country and across sections of the country.

And I think that, while we do want it to align with the popular vote, that creates a more moderate majority. It forces candidates and parties to take into account more of the country than they might otherwise, more than just their base. And I think that makes it so that more interests and more of the common good is realized in that kind of election—that I don't think happens with a popular vote.

HEWITT: Now, Jamelle responds to that by saying, “Take rural representation. If you conceive of rural America as a set of states, the Electoral College does give voters in Iowa or Montana or Wyoming a sizable say in the selection of the president. If you conceive it as a population of voters, on the other hand, the picture is different. Roughly 60 million Americans live in rural counties, and they aren't concentrated in ‘rural’ states.

“Millions live in [large and] mid-sized states like California, New York, Illinois, Alabama, and South Carolina.” Pause there, because I missed the word large. And, you know, it's obviously a large state. “With a national popular vote for president, you could imagine a Republican campaign that links rural voters in California—where five million people live in rural counties—to those in New York,” with roughly 1.4 million people.

“In other words, rural interests would be represented from coast to coast, as opposed to a system that only weights those who live in swing states.”

CARRINGTON: I think that what you have to understand, too, is that rural voters in different states often can have a similar interest. And that even when you're—and that, by being forced to run in moderate states—swing states that have sizable rural populations, you actually are forced to cater to the needs of rural voters in that way that I'm not completely convinced that you would have if you had that national system.

And my other response is that—you mentioned this, Hugh—that we're not just looking for that. We're also looking for representing the states. We are a federalist system. We believe that the states have a real say and a real place. And so we want to keep the integrity of states as states as part of this conversation as well, that that isn't that—

HEWITT: Is it the response that, Professor, that the one part of the Constitution that cannot be amended by the explicit terms of the Constitution is equal representation of the states in the Senate? So we always have a backstop there.

CARRINGTON: We do. We do in the Senate, but we also—one thing to keep in mind is the president is the one officer that the entire country chooses. The entire country doesn't choose Nancy Pelosi or Mitch McConnell, even if they're the leaders of their particular legislative body.

The president is the one officer that everyone chooses, so I think it makes sense that we would bring every subset of the system to bear in making that choice, that we would not only bring the national will, but we would also bring in what the states think, because this is the one representative of the entire country as a whole, in and of him- or herself.

HEWITT: Now, last quote from the Bouie. In 2016, “Sam Wang, a molecular biologist at Princeton…found out that of almost 400 campaign stops made after the conventions, neither Hillary Clinton nor Donald Trump made appearances in Arkansas, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, the Dakotas, Kansas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Mississippi, New York, South Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, or Vermont.

“It doesn't matter that Trump won millions of votes in New Jersey, or Hillary Clinton won millions of votes in Texas. If your state is reliably red or blue, you are ignored.” Now, I argue that's not true, because we have a national news media. And we live in an age of technology and internet availability of information.

But it does take the president—he can't gin up. There's no point for him to go campaign in West Virginia. There is no point for Hillary Clinton to go campaign in West Virginia. We have a three-state election, in essence—Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, Adam. Is that bad?

CARRINGTON: I don't think that it's bad in the sense of, why are those states the focus? They've become the focus because in many ways, they are a microcosm of the country. And, therefore, to win those states is to craft a nationally palatable platform. And I think another thing you said about the media—I worked on a presidential campaign back in the day.

And the big thing that a lot of the campaigns were pushing for rallies and visits was news media coverage. And that news media coverage, of course, was partly local. But the idea was that this was a way to reach the national audience and to do so in a way that, since you are running in a swing state, you're placating or pitching to the average American voter.

And I think that that is something that, sure, that means the president doesn't personally visit every particular state on the campaign trail. But the swing states are a swing state for a reason that shows a national vision of his messaging, a national vision of what he thinks is the common good for the country.

Otherwise, these other states would become swing states because the people would say, your message is out of touch with our interests and our values.

HEWITT: I'm also deeply skeptical of the abolishment of Electoral College because of its secondary impact on polling. It would increase dramatically the impact of polling on the race, in that people want to go with the winner. And, if there isn't a path for someone, they go with the winner.

I think it's got to be on some people's minds. This will end up being conclusively decided long before the election balloting is done.

CARRINGTON: Well, and that's also why I'm against early voting of any kind. I think that campaign can change in the last couple of weeks. And I think that, also, the problem, too, is one of the difficulties with the national popular vote is getting a clear majority—that the Electoral College demands that you win not just a plurality of electoral votes, but a majority.

And I think that that's not only good for legitimacy, I think it's also good for the moderation of the kind of coalition you try to build that I've talked about before. And I think, with the national popular vote, you have a lot better chance of five or six people jumping into the race, and the winner—if it's a plurality—being 35% of the vote.

And imagine the legitimacy problems if that was all you had to hang your hat on, 35% of the American people. I think that's a much bigger problem with the popular vote and much more likely constitutional crisis if it happened.

HEWITT: Now, it's not a constitutional crisis if an election goes to the House, because it's provided for in the Constitution. But it would certainly be controversial, and I've written a column. Howard Schultz's path to the White House is by winning one state of sufficient electoral size that it throws it to the House. And then he basically blackmails the Democrats to elect him president. Do you fear that? Do you fear an election in the House?

CARRINGTON: I don't fear an election in the House happening. I do fear an election in the House being the norm, because I think it's the problem with the divergence between the popular vote and the electoral vote on steroids, to be honest, because one reason they didn't want the House selecting the president normally in the Constitutional Convention is twofold: One, worries about the independence of the executive. Gouverneur Morris, one of the Founders, says, the president will become the creature of the legislature, which will undermine separation of powers. The second is there's a lot more problem if intrigue, log-rolling, and buying off—

HEWITT: Amen.

CARRINGTON: —in a set system like the House, and especially the House and Senate the way they are now. So I think that's another problem where the House should be only extreme breakdowns of the system. And I think also just—

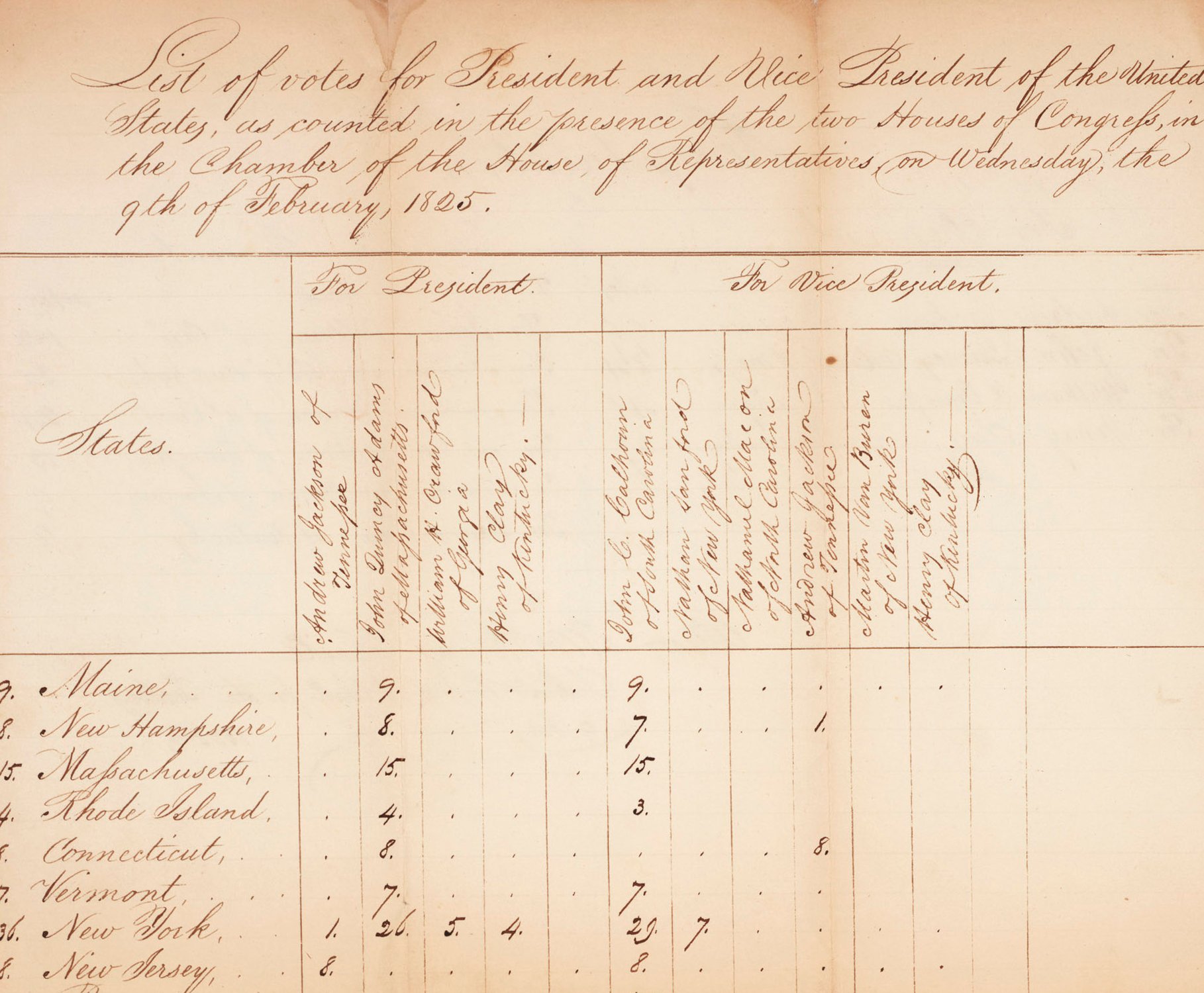

HEWITT: We've never had one. Well, we had one. We had one. We'll come back from break and talk about that one instance and what we might expect in 2020. Don't go anywhere, America.

GEORGE III: And when push comes to shove, I will send a fully armed battalion to remind you of my love.

HEWITT: Welcome back, America. That's Hamilton. My guest, Adam Carrington, teaches a bunch of courses at Hillsdale College. One of them is Hamilton: The Man and the Musical, and that's King George singing in Hamilton. We have direct democracy in Great Britain, with a parliamentary system. And it's totally broken down, Adam Carrington. Do people not connect those dots?

CARRINGTON: No, I think that they, again, overestimate human nature. And I think they underestimate the separation of powers, because that's another thing, I think, that the Parliament and the English system don't have the separation of powers system that we have. And I think that's to their detriment as well.

HEWITT: Now, let's conclude our conversation this morning with—Can we actually win the argument? This is a very practical issue that I think would appeal to Hamilton and others. The Electoral College is easy to denounce. It is denounced repeatedly all day long on the Liberal cable networks and on Liberal social media, because it is poorly understood. Is the argument capable of being won? Or should we hope the Democrats go into that box canyon and never emerge from it?

CARRINGTON: I think it is winnable, although I think it's going to be hard, because there is great power to the argument that the one with the most votes should win. But I think that we just have to constantly reinforce that the Founders built a system that was built on—what kind of goods do we want to result from the election process? Not merely that choice is the beginning, the alpha and omega of democracy.

Good popular government involves ordering our choices in a healthy way. And I think that's the argument that we have to make.

HEWITT: Now, how much of this is related to President Trump's style? Peggy Noonan has a great piece in The Wall Street Journal today saying, he didn't just blow open the door. He blew it off the hinges, and he created jagged edges.

He grew so big with such tough rhetoric and such direct politics that it's really polarized all of American politics, producing what she calls the “mean girls of Congress,” Representatives Omar and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. What do you make of that argument, that Trump has really made this the central issue of the day?

CARRINGTON: I think that what's happened is partisanship has become so deep and defining in the current era—and the reaction to President Trump has been a big part of this on the Democrat side—that they are willing to not see themselves the way Americans need to see themselves, which is, on one hand, yeah, you need to be a partisan.

You need to be on a side as best you understand it. But, on the other hand, you need to be an American citizen and dedicated to the Constitution. And I think they've now decided that any means, as long as they see it as undermining the president and their opposition is fine. And I think that's not healthy for a republic. It's not healthy for a constitutional government.

HEWITT: Well, the good news is we have term limits. So, at most, it can go on for four more years, and then the reversion to the norm that always occurs in politics. And I do believe in the reversion of the norm. Our normal situation is the Electoral College follows the popular vote. It's usually a very abnormal situation, and 2016 was one of the most abnormal situations ever, given the two leading party candidates.

Just doesn't alarm me in terms of history, but changing the basic structure does. It really does. But I don't think it's possible, so I don't know whether or not to worry about it. Last minute to you, Adam Carrington.

CARRINGTON: I don't think you should worry about the system changing. I think we just need to worry about civic education, to make sure that the people trust and have confidence in the system and don't check out. And that's the kind of stuff that we're trying to do at Hillsdale, both with our own students and with others.

And I appreciate that you let Dr. Arnn and then me—this time—on to do these kind of things, because it's a great civic service, to bolster good citizenship, which is the bulwark, really, to the greater concept that the Electoral College is trying to accomplish.

HEWITT: We've got one more minute. Let me add this, though. The breakdown of civics in secondary and junior high education is complete—I mean, it's completely shattered. How do you rebuild that?

CARRINGTON: We're trying to rebuild it here with our charter school initiatives. We're trying to do it with our online courses. We're trying to do it, and other places are trying to do it by getting back into the public schools and at least giving willing teachers tools to do so. And I think it just has to be a large civic effort.

And we're going to—no victory or defeat is ever completely assured. But we're going to either win or go down fighting on that front.

HEWITT: Adam Carrington, professor at Hillsdale College of many, many things. Thank you, my friend. A great conversation today. This will be posted, along with every other Hillsdale Dialogue from 2013 forward, for your binge-listening pleasure at HughforHillsdale.com. I think we'll call it “Electoral College” so that people will just go to know and find it there.

And remember, all things Hillsdale are available at Hillsdale.edu—that's Hillsdale.edu—including all the fabulous courses—many, many of them—30- and 40-minute courses on World War II or “The Second World Wars,” as Victor Davis Hanson and Larry Arnn referred to it, one of the most magnificent of the recent offerings.

Course in Progressivism, the assault that actually has led to this election cycle that we're in now with the Progressive left. One or two on the Constitution. They're all there. They're all free. They're all for your viewing pleasure. If you're a teacher, adopt your curriculum from that. If you're an interested citizen and you want to improve your own knowledge of how the system works, it's all right there at Hillsdale.edu. Thank you, Dr. Carrington.