Intellectual Curiosity: A Virtue or a Vice?

Share

By Hillsdale College Online Courses August 28, 2015

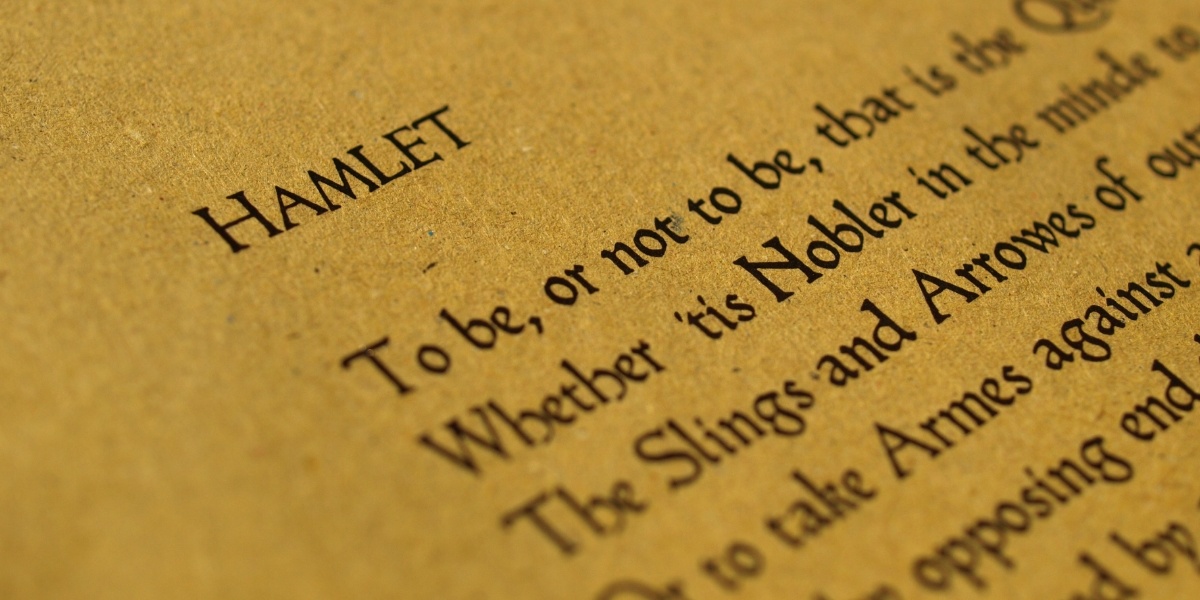

John Miller and Stephen Smith discuss Shakespeare’s understanding of intellectual curiosity, which can also be characterized as intellectual intemperance. In Hamlet, the Prince’s curiosity betrays an inability to govern his mind, and to bring it under the subjection of virtue, even, according to Dr. Smith, playing a role in his death.

The following video is a clip from Q&A 3 of Hillsdale’s Online Course, “Great Books 102,” featuring Stephen Smith, professor of english, holder of the Temple Family Chair in English Literature, and dean of faculty, and John J. Miller, director of the Dow Journalism Program.

Transcript:

John J. Miller:

Horatio also says, ‘don’t consider things too curiously’ to Hamlet—that’s a warning. You seem in your lecture to think that’s a good warning. On the other hand, I've always thought [that] intellectual curiosity [is] a good thing. Don't we want that in people—even in leaders?

Stephen Smith:

Well, this is when . . . our modern use and Shakespeare, or the earlier use, is at odds. Whenever I fill out a recommendation form, [for my students] there will be a box for intellectual curiosity and I think to myself, “you know, you're asking me to praise a vice,” . . . but that's because I've been studying this older sense of curiositas. What curiosity is earlier in the tradition is not a virtue, it's, in fact, a vice! It's intellectual intemperance. It's the inability to govern the intellect. You just let it wander, you let it rove, you don't pay attention to what you should be paying attention to.

Think of ‘to be or not to be, that is the question.’ Is it?! Is that the time to be addressing that subject, right at that point in the play? But Hamlet loves that kind of – and so do the readers, [they] like it too. But curiosity didn't just kill the cat, it killed the prince I think at the end…. One of the key lines in the play reveals, I think, Hamlet's most, well, one of his biggest problems, which is intellectual intemperance. That's his greatest gift, that intellect of his, that's why he's so famous, that's why we like his soliloquys, we like his monologues. He can't govern the thing, John! He can't bring it under the direction of virtue. And it gets him, increasingly, into trouble and then plays a part in his death too.

So that warning against curiosity on the flip side, positively, is: we need to learn to discipline our intellect so that it can do what it should do well and not rove beyond all bounds, think about anything at any given time. ADHD, if you will, morally.