Kavanaugh and America's Turning Point

Share

By Hillsdale College September 7, 2018

HUGH HEWITT: Morning glory, America. Bonjour-- hi, Canada. From the ReliefFactor.com Studios inside the sweltering beltway, the swamp is indeed a swamp. I am Hugh Hewitt. That music means it is time for The Hillsdale Dialogue.

The last radio hour of my week is always with a member of the faculty or team at Hillsdale College-- usually Dr. Larry Arnn, the president; often Dr. Matt Spalding, the Director of Hillsdale College's Kirby Center, that lighthouse of sweet reason, that lantern of freedom in the shadow of the Capitol.

And it is indeed Dr. Spalding this morning. Matt, welcome. Are you Spartacus?

MATT SPALDING: I am Spartacus.

HEWITT: What did you make of that moment? Before we go large, let's go small-- Cory Booker.

SPALDING: Well, it's both small and large, right? I mean, small proves the large, which is is theater. But I think-- well first of all, I just think he made an embarrassing mistake. He was competing with Harris about positioning for the 2020. He thought he had something. It turns out it had been previously released, which completely undermines his position. It also turns out that Kavanaugh was the recipient of the email chain originally, and it also turned out that Kavanaugh was opposed to racial profiling.

So I think this is an example of a politician who does move very quickly when he thinks he has something, and he stepped on it, and then this-- this is his absolutely ridiculous Spartacus moment. I was trying to think of a parallel. This is really a Tom Sawyer moment, right? You recall Tom Sawyer, right? He fakes his own funeral to show how great he is.

I mean, this was a setup. This was completely theatrical in order to show that he's somehow being civilly disobedient by releasing documents. So I think this is actually going to hurt him considerably. Although I looked at The New York Times this morning, there's really no mention of it hardly.

HEWITT: Well, I gotta say-- Marco Rubio--

SPALDING: --a serious thinker.

HEWITT: Marco Rubio just tweeted out-- to your point, he just four minutes ago tweeted out, "On this day in 718 BC-- or 71 BC, the Thracian gladiator Spartacus was put to death by Marcus Licinius Crassus for disclosing confidential scrolls. When informed days later that, in fact, the Roman Senate had already published-- publicly released the scrolls, Crassus replied, oh, OK. My bad.

SPALDING: Exactly. I think he really looks pretty silly. And in the presidential primary, if you will, the Kavanaugh primary, I think Harris, although she looked serious-- wasn't that serious as well, but she was actually much more aggressive. And I think in terms of how the left looks at this, she won that debate with Cory Booker.

HEWITT: In fact, Amy Klobuchar and Chris Coons were both serious, substantive, tenacious, though wrong, and a Klobuchar-Coons ticket would be something.

Let's go to 30,000 feet. Your assessment of whatever you want to talk about of Judge Kavanaugh's two-day ordeal-- if you want to call it an ordeal-- you just have to sit there and listen to a lot of nonsense. But what did you think, Matt Spalding?

SPALDING: I was struck in watching it. It really was two parallel universes. You had Kavanaugh who gave an excellent testimony. He did extremely well and took serious questions and bantered with them in a serious way. He was actually testifying. That was actually a hearing.

But then parallel to that, in another universe, we had the protests, and we had positioning for the 2020 campaign, and we had a divided Democratic Party trying to figure out these debates on the documents. All of which, by the way, I don't know if you've picked this up, but was made apparent by this rules discussion which forced McConnell on the second day to temporarily close down the Senate. I don't know if you followed that. But that just proved that this was theater.

HEWITT: Yep.

SPALDING: The Democrats could have shut down the committee hearing because by one of these great Senate rules, you can't have the Senate and this committee occurring at the same time, but instead they had a consent agreement to allow the hearing to continue. They could have shut it down. But they didn't. They wanted that hearing precisely for that moment.

So you had theater on the one hand, which is really kind of the way that political debate and the way that that side-- that base is pushing, and the other side trying to have a serious hearing with an excellent candidate. And I think this reveals a lot about American politics right now, which is this divide which is getting larger as we go. But he did a wonderful job, I thought.

HEWITT: And I want to ask about one area in particular of concern to my pro-life friends. And I'm talking with Dr. Matt Spalding of Hillsdale College. Hillsdale.edu for all things Hillsdale. HughForHillsdale.com for all the Hillsdale dialoges which date back to 2013. Sign up for Imprimis, by the way. It's the absolutely free newsletter from Hillsdale.edu. And there are many online courses, including courses on the Constitution that you ought to watch if you want to understand what went on.

In the first exchange he had with Senator Feinstein, the ranking minority member, Senator Feinstein pressed him on Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. And Judge Kavanaugh said, Planned Parenthood v. Casey is precedent on precedent. Which is troubling to some pro-lifers because they thought that verged close to super precedent, meaning it couldn't be overturned, but then he upheld as the greatest decision-- the greatest moment in Supreme Court history, Brown v. Board, which overturns Plessy v. Ferguson.

SPALDING: --overturned, right.

HEWITT: And Plessy was a precedent on precedent. And so I think it was, if you read the whole thing, nobody knows what he's going to do, but as Mitch McConnell told me yesterday-- I'll play the tape-- nobody really knows what he's going to do, and that's just what the Framers intended.

SPALDING: Well, I don't know if I'd go so far to say no one knows what he's going to do. I think we know what he's going to do in the sense that he's going to make these decisions in light of the Constitution. And there's a certain similarity here with the very idea of judicial review in the first place.

So the email that was released that supposedly shows he has no concern for precedent on the Roe case, which I think is not a strong case either-- and this seemingly referenced a precedent on precedent, which his concern is a reference back to-- that was I think Arlen Specter talking to Roberts at his hearing about his super precedent.

The problem you have here is how to understand the role of precedent. And like judicial review itself, the idea is that you look at it case by case in light of the Constitution. And I think his parsing was actually quite good, and I don't have concerns about it. Actually, I was very heartened by his language and how he's thinking that through.

I mean, the time between Plessy and Brown is what, 58 years. I thought-- when I went back and looked at what I thought of, Justice Roberts' concurrence in the Citizens United case--

HEWITT: Yep, the key issue--

SPALDING: --in which he talked about precedent. And he walks this through. It's kind of stuck in the middle of this concurring opinion. And it's an excellent laying out of what precedent means and what it doesn't mean. It's not inexorable. It's not mechanical. It's a principle of policy.

It's a rule of thumb.

HEWITT: And there are factors in state decision..

SPALDING: --can't turn around.

HEWITT: Yeah. There are some factors, like reliance, which would hold Obergefell, you wouldn't want to upset that. But there isn't reliance in the case of people who are not yet pregnant. And political factors-- did the society accept what you decided? And it clearly didn't with Brown v. Board-- thank God. It didn't accept Plessy. And it hasn't with Roe.

And so I think-- you have an argument it could go either way, although a lot of pro-life people were upset with that.

SPALDING: What it does show us is one thing here that is unknown, this is a prudential question, as in jurisprudence. If you're going to overturn a precedent, one way to do it is, as soon as you get five votes, overturn a precedent. The other way to do it is, well, we need to be careful here. This has been around a while. We need to get around the edges, bite around the ankles, and box it in somehow so that at the end of the day, it's kind of an empty shell.

There are different ways in which you can go after precedent without doing it in a politically overt or large scale way. And I think he might have a much more nuanced view of that, as well as Justice Roberts.

HEWITT: Absolutely he does. When we come back, I'm going to play for Matt Spalding some of the clips of the majority leader's comments to me about the Kavanaugh confirmation, which I played in the first two hours, to get his reaction to them. The entire audio and transcript of my conversation with Senator McConnell is posted over at HughHewitt.com.

Don't go anywhere except the Hillsdale.edu. That's where you go to get everything Hillsdale. Great sponsor of this program and a terrific lantern in the north and a lantern in the shadow of the Capitol for first principles and freedom. You probably have viewing parties at the Kirby Center, am I right, Matt Spalding?

SPALDING: There were comedy parties at some point.

HEWITT: Well, I keep telling you. That's the only place in town other than my living room that I know had 24/7 C-SPAN coverage on, because the cable networks cut away. They didn't follow the whole thing till the end. They'd given up. They can't stop him.

SPALDING: No, no. They just wanted to show good trial parts, but the actual serious parts of the hearing were excellent and of very high quality.

HEWITT: They were. We'll be right back. Don't go anywhere, America. Dr. Matt Spalding, Director of the Kirby Center. Follow the Kirby Center on Twitter, follow Hillsdale on Twitter, @Hillsdale. And then go to Hillsdale.edu. Sign up for Imprimis, absolutely positively free, and all those free online courses. And if you're a young college student, go and apply today. Go to the lantern of the north. Stay tuned to The Hugh Hewitt Show.

Mitch McConnell, thanks for sitting down with me today.

MCCONNELL: Yeah, glad to be with you.

HEWITT: You've said many times that Judge Kavanaugh will be confirmed, and that your major power is controlling the calender. So the question is, when will he be confirmed?

MCCONNELL: Before the end of September, he'll be onboard at the Supreme Court by the first Monday in October, which you and I both know is the beginning of the October term.

HEWITT: Any doubt in your mind about that result?

MCCONNELL: None whatsoever. I think any doubts anybody might have had have been dispelled by his virtuoso performance before the Judiciary Committee. I mean, it's stunning. He's just a stellar nomination in every respect.

HEWITT: I'm going to come back to the specifics of his performance in a moment, but you've got 26 appeals court judges confirmed. This will be your second Supreme Court justice confirmed. There are 10 more in the queue who've already been nominated. Do you expect those 10 to be confirmed before the end of this session?

MCCONNELL: Yeah, we're going to clear the deck of all the circuit judges, as you have reported repeatedly. And I appreciate the attention you're giving to it. I think it’s among the most important things we've done, not just the Supreme Court justice, but the circuit judges. We've set a record for the first two years of any administration. If we can hold onto the Senate for two more years, we're going to transform the federal judiciary with young men and women who believe in the fundamental notion that the job of judges is to interpret the law as it's written.

HEWITT: Welcome back, America. I’m in Studio inside the beltway with Dr. Matt Spalding, Director of the Kirby Center, Hillsdale College's outpost of reason in the Capitol. Matt Spalding, what do you make of Leader McConnell's certainty and as to the record thus far on judges?

SPALDING: In terms of certainty, I think he's absolutely right. I think the fact that we're seeing this theater is because they really don't have something to go after and they really don't have a serious argument about his appointment. I can't remember his name, but the fellow judge who helped introduce him who is a Ruth Bader Ginsburg judge, fully endorsed him as an excellent, excellent, qualified judge to be on the Supreme Court, so I think he is absolutely right about that.

I think McConnell's record with what he's done with judges-- I think they have, is it 60 now, and the internal goal is 100 by the end of the year?-- is truly his legacy. I think that's the way he understands it. I would like to see him put it in broader and more elevated constitutional terms, beyond: all I can do as majority leader is control the calendar. I'd like to see more revival in Congress, but having said that, this is an excellent thing that he's done in terms of reviving that. This will be a legacy that will survive a long time.

And I think that given the maturity of conservatism and the development of these judges, because this goes back a long way in terms of the revival of this argument about how to interpret the Constitution, and now these are the kind of appointments-- and they're young appointments and the sheer numbers-- this will actually have a significant, significant effect on the judiciary, but as a result, a lot of our politics.

Because if you go back and hew to a stronger sense of what the Constitution did in terms of not only the Court's understanding of things but the presidency and Congress, that will really point us towards the revival of the other branches, and thus the separation of powers, which I think is really the ultimate goal here. It's not a policy or political outcome, but it's a revival of constitutionalism. And I think that's the goal. And I think in hindsight we'll look back and Mitch McConnell will have a significant role in having done that as majority leader.

HEWITT: And indeed, we'll talk about that-- and I'll play for you what he said about his legacy. He also said that the Ginsburg standard, which Judge Kavanaugh frequently invoked, I want to quote, "after what happened to Robert Bork," McConnell said, "every nominee of every president since then has not speculated on what they might rule in the future," and that's not going to change, Matt. Do you agree that that's a good development?

SPALDING: Yes and no. On the one hand I think they need to be careful not to get caught up in things. But I would like to hear more about how judges think. I think Kavanaugh gave us some of that, but they tried to Bork him by getting him caught up on political questions and who we know, when, where, and what. And so he had to do that. It's unfortunate. I think they shouldn't talk about coming cases, but we should know how they think, how they interpret the Constitution, and where they are on that.

I'd like to hear more. We heard a lot of very good things from Kavanaugh, but more is always better.

HEWITT: I'll be right back with Matt Spalding of the Hillsdale Kirby Center in Washington, DC. All things Hillsdale at Hillsdale.edu. All of my previous conversations for your binge listening pleasure, with Dr. Spalding, Dr. Arrn, other Hillsdale faculty, all collected at HughForHillsdale.com. Stay tuned, I'll be right back.

And I want to go back to Judge Kavanaugh, the focus of this. He invoked yesterday among his many favorite Federalist Papers in response to Senator Lee, Number 69. That's by Hamilton. In Federalist 69, Alexander Hamilton says, "A president may only be impeached, tried, and removed, and then subject to criminal process."

You're a lawyer, a good one, and the leader of this body. Do you believe a president can be indicted?

MCCONNELL: I'm a lawyer, but not a good one. The Justice Department, I gather, has taken the position under presidents of both parties that the appropriate remedy for presidential misbehavior is impeachment. I'm not an expert on this, but I hear that's the case.

HEWITT: Do you think he is subject to subpoena? Judge Kavanaugh delicately avoided answering that.

MCCONNELL: Yeah, that'll be up to the courts to decide. I have no idea how they would rule.

HEWITT: Stop right there. I am Hugh Hewitt in the ReliefFactor.com Studio inside the beltway. I am joined by Dr. Matthew Spalding, Director of the Kirby Center, Hillsdale College's lighthouse of sweet reason in the shadow of the Capitol. You can find all things Hillsdale at Hillsdale.edu. All of our Hillsdale dialogues, of which this is one, are collected at HughForHillsdale.com for your binge listening back to the founding of literature, actually.

Matt Spalding, what do you make of that? Can a president be indicted? Can a president be subpoenaed?

SPALDING: I thought that was a good point. I, of course, perked up when I heard him talking about his favorite Federalist Papers and took careful notes.

HEWITT: We're such geeks. You and me both. And Mike Lee, you, me, and it actually is what the Democrats ought to focus on with 69.

SPALDING: Well, if they would look at them and take them seriously and ask those questions, that would have been a very interesting conversation.

Look, I think McConnell gets the point here. I wish they would stop making this reference to, well, the courts will have to decide this. I don't like that. Political leaders, especially the senators, should generally have a good sense of this.

And the problem is, this is a broader separation of powers problem. And I don't think the president can be subpoenaed while he's president. In 69, it's clear that the remedy is impeachment. You can't indict him while they're in office. These are political questions.

Which is to say that the political officers-- the Congress-- they should have an opinion, because it's a political question. It's not something that's going to be left to the courts.

HEWITT: Now it might have been prudential for him, right? It might have been prudential for him not to answer yesterday. But I believe Clinton v. Jones now is wrongly decided, and we have seen the consequences of not only civil, but God knows what a criminal proceeding would be directed at a President. And Hamilton's very clear, Matt. And I think you and I have the same opinion of what Hamilton and the Framers had in mind, which is, the President is running a government. If you want to take him out, take him out, and you can do it quickly, but you do not cripple him with a thousand lawsuits.

SPALDING: No, that's exactly right, and that's precisely why it's a political question, right? These are prudential judgments, so it's not a legal question. It should be deferred to the political branch and they should impeach him-- that is the remedy.

The other-- can a President pardon himself? Now there's a hard one. The legal community is somewhat split on that. I think he probably actually can, precisely for the same reasons. I'm much less comfortable with that. But that's a political question if he tried to do that, right?

HEWITT: And I haven't done my homework on that yet. I have not read The Federalist Papers on the pardon power sufficiently recently that I could actually give you a studied opinion, but I do know what I know about 69. And impeachment, trial, removal, and then ordinary criminal proceedings. That's almost a direct quote.

SPALDING: That's also how they discussed it at the convention, right? They talked about the presidential removal. This was debated in coordination as they were developing this idea, well, we have three branches, each branch plays a certain role, the removal question is a political question. The essential quality of separation of powers is we have to preserve room for those types of questions. And ultimately, when we say it's a political question, it also means it goes to elections.

Namely you defer to the American people. These are large questions. And they're not tactical legal questions. And one of our problems today is everything is becoming a technical legal question, which gives judges way too much authority over way too many things, which is a very large problem. But more importantly, it just removes certain things.

It's like setting regulatory questions to the bureaucracy. More and more things are being decided in places where there's not an open political discussion. You can't kind of have the back and forth of a deliberative process. But it's separate from and isolated from the role of consent that the legislature gives you, or in presidential elections, the election of the president gives you.

This kind of question was to go to that. That's what impeachment means. It's a prudential question that the legislature will make as to what is a high crime and misdemeanor. We can talk about the historic precedents, but ultimately it's a question for them to decide.

HEWITT: My guest is Dr. Matthew Spalding, Director of the Kirby Center, Hillsdale College's office and studies center in the Capitol. As a professor of constitutional law, I have to teach this once a year, maybe twice a year. I have to try and explain the difference to my newbies, my second years who-- they're diving in. Most case books start with Marbury. They skip the Constitution. They do not know what originalism is, they do not know what textualism is, they do not know what constitutional textualism is, and they definitely don't know that original intent is not what those first three things are.

But judge Kavanaugh sat down and he parsed them all out. I thought that was a high point for teachers, Matt Spalding. A very high point.

SPALDING: Yeah, I thought he was just excellent on those things. And he kept pulling it back to these broader elements. His discussions of The Federalist Papers and how he weaved that into his testimony was very good. But even to take a step back from that, from a broader teaching point of view, coming back to our overall view of these hearings, I think what we're seeing now-- and now it's become open as a political debate-- this is not a debate about, well, is he a textualist or an originalist, right? We're not parsing those things anymore.

If you want to see the difference between the different types of originalists, go to a Federalist Society conference and see them debate these questions. There's a serious debate there about constitutional questions.

But broadly what we see in this hearing is a debate between originalism writ large. This general idea that you should go back to the document and its laws passed underneath it with some role of precedent is the thing that is your guiding light. That's the general argument being made here by Kavanaugh and judges like him, versus kind of a non-originalism, or what is usually called non-interpretism.

Which says that the Constitution itself is actually a minor factor. It's all about how do we update it, it's a living Constitution argument, or how do we use it and make a broader political argument separate from the Constitution, or find things in its numbers and emanations. I think it's really important to not only understand the particulars of types of originalism and textualism and things like that, but just to see broadly. See the forest for the trees here. This is not that debate.

HEWITT: And boy is it not. And I want to play for you next about the importance of what McConnell is doing here. Cut number four from the McConnell interview.

Penultimate question. Is this your legacy? Beginning with the decision to hold open the Scalia vacancy because of the death of Justice Scalia through the organization of the appeals and Supreme Court nominee? Is this the most important part of Mitch McConnell's legacy?

MCCONNELL: I think so. I think it's the most consequential series of things that I've done that have the longest impact on the country. In the legislative process, Hugh, there's not much you can do all by yourself. The one thing the majority leader can do that no one else can do is the schedule-- what you will do or what you will not do.

I think the decision not to fill the Scalia vacancy was the most consequential decision of my career, and I think the follow-up on that to not only fill the Supreme Court vacancies, but put in place men and women who believe that the job of a judge is to interpret the law into as many places as we can, particularly at the circuit court level, for as long as we're in the majority is the most important thing I will have been involved in in my career.

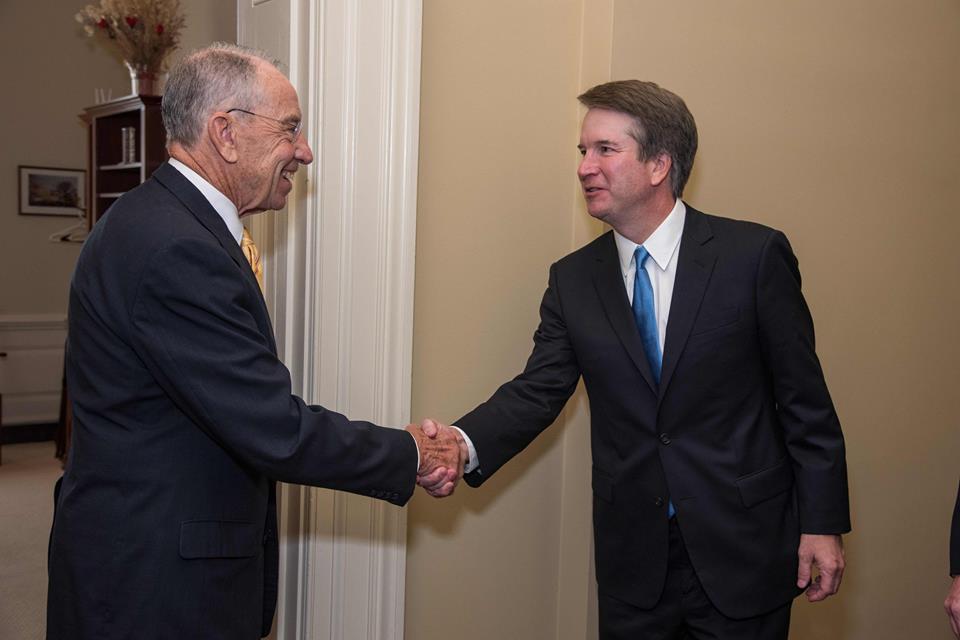

HEWITT: All right, now, Matt Spalding, I have an op-ed coming out in The Washington Post today where I say, it is not overstatement to say that decision after the sudden and shocking death of Justice Scalia by Mitch McConnell and the subsequent action of he, President Trump, Chairman Grassley, has saved the Constitution as we know it-- meaning as amended and as interpreted through the end of this term. I don't know what they're going to reverse, I don't know what they're going to change, but I do know it's not going to be a radical lurch to the left because of that decision by Mitch McConnell and the nominee sent forward by President Trump and the proceedings by Chairman Grassley and the GOP caucus. Do you agree with me?

SPALDING: I do. It's important to understand the potential turning point there, right? Merrick Garland, to fill the Scalia seat, that was a-- that would've been a very significant shift, and so not doing that and getting Gorsuch in was a holding position, which then set up this nomination of Kavanaugh replacing Kennedy.

And of course, that's exactly what is to happen in politics. The President appoints, the Senate approves. The key thing here is what McConnell did, which I think is historically defensible and proper, but he had the foresight to understand that, and I think under the circumstances, did exactly how one should do, right? The idea of constitutional actors, whether the President, a member of Congress, a Supreme Court Justice, they're to uphold the Constitution as they carry out their duties, right? That's precisely what it means.

And McConnell really did that. He's got an understanding of the Constitution. He sees his role and he's using the tools he has at hand, namely the calendar, the schedule-- the ability to control and use the Senate to do its constitutional duty of advise and consent.

So I think it was a key turning point. We don't know what's going to happen and where this goes, but I think if you look at the longer history of the direction, the trends of the courts, this is exactly what one of the important things politics is about, appointments with the other-- one of the three branches is determined by elections. This is precisely what it's been about, and I think in hindsight that will be seen as a major threshold turning point.

And so McConnell is right in seeing that as his legacy, which I hope there's a lot more to that as we now try to rebuild Congress. And I think you're right that that will be a major turning point for the history of the Constitution.

HEWITT: It's a major point in constitutionalism. When we come back, I'm going to talk with Matt Spalding about the counter-factual. What if a President Clinton had appointed a Stephen Reinhardt-like justice and then Justice Kennedy had retired and President Clinton appointed a second Stephen Reinhardt-like justice? The counter-factual here is what people have to focus on, because we were that close, people. And these other 26 appeals court judges matter as well and the 41 district court judges, but the 26, soon to be 36, and maybe 46 by the end of this term-- it depends if the White House Counsel's office gets its act together.

When we come back, we'll talk about the counter-factual. Don't go anywhere. The McConnell interview is posted, audio and transcript over at HughHewitt.com. Matt Spalding, we'll be right back.

Welcome back, America, to the ReliefFactor.com Studio inside the beltway. I am Hugh Hewitt. Dr. Matt Spalding is my guest. Dr. Matt Spalding is my guest from Hillsdale College's Kirby Center in Washington, DC. All things Hillsdale in this Hillsdale dialogue hour, the last radio hour of the week, are found at Hillsdale.edu.

Dr. Spalding knows his con law, knows his constitutional history. So I present the counter-factual-- if President Trump had been defeated and we had President Clinton, and she had filled the Scalia seat and had filled the Kennedy seat with people like Stephen Reinhardt, how significant would that be to our history?

SPALDING: Very, very significant. But I want to parse this a couple of different ways, because it is a very significant question. I think we don't want to miss or under-emphasize it.

Today I think we suffer from a couple of problems. For a lot of people they think of the Constitution and they think it's merely legalisms and it's for judges. And so for many people there's not that much interest in it. The nomination comes up and they get a particular interest, but they-- on the left, on the right-- generally tend to be concerned about policy outcomes. “Well, I'm concerned about the protection of human life and unborn life,” or “I'm concerned about the Second Amendment.”

Those are legitimate questions. I don't mean to diminish them. But I think there's a much larger thing here, which we've already alluded to in the previous segment, which is this larger trend of the type of rule and the type of government under which we live. This question is not resolved. There is essentially a broad, low boil of a constitutional crisis going on about what kind of government we're going to have and who's going to rule it.

So I would put it in those terms. It's not about making up a list of this particular case would have been different or that particular issue would have been different, although there are lots of those which are extremely significant. I think this is a question between whether we continue down a path towards expert rule-- and remember, judges in many ways, are just another form of expert rule, which the progressives advocated-- we mostly think of that in terms of the bureaucrats, right?

Ruling us through their decisions or their regulations, as opposed to trying to reestablish-- not in one fell swoop, but over time-- to revive a sense of constitutional rule, of trying to rein in the modern administrative state under the executive, of trying to push towards a stronger exertion of congressional powers and legislative authority, of trying to actually limit the decisions the Court makes and make them make more constitutional decisions as opposed to making up arbitrary rules and tests. Which points us towards a revival or a semblance of self-government and the lifeblood of what it means to be a republic.

So I think it's a much more significant thing here that I think the American people need to think more broadly about. These appointments are extremely significant, which is why I emphasized last time that this wasn't merely a debate between liberal constitutionalism and conservative constitutionalism. This is really a debate between the Constitution and constitutionalism and what it means today, and it's a form by which we are ruled and we self-govern under these rules-- a rule of law system, or we're going to continue going down a path and really turn it over to unelected experts, either bureaucrats or judges that don't respect the Constitution.

That's the question before our country. That's the larger question we face, now and for some time, and I think these appointments are going to be a significant contribution towards at least getting the courts in line on these questions so that we, through the elected branches of government, can start ruling ourselves.

HEWITT: 95% agree. But there is one thing that deserves special attention-- the redistricting cases. Because if the judges had, as Stephen Breyer wished they had-- he's always called it his greatest disappointment-- gotten those two judges-- if the living Constitution enthusiasts had gotten those two vacancies, redistricting would be stripped from the states and put in the hands of Democrats, increasingly left-leaning democratic judges you point out especially.

And the right of the people to decide how redistricting occurred would have been gone, and that is a fundamental challenge to the way we we represent ourselves.

SPALDING: I completely agree. So let's say 100%, you're absolutely right, but I would think that's consistent with the broader brush I've painted with here, which is, that's an example of judicial experts taking over and taking something--

HEWITT: Yes.

SPALDING: --away from legislatures based on consent. That's a political question. And that would be an example of continuing in the wrong direction, and that one in particular would have had a large effect as to how this continued going forth. This doesn't solve this problem. Let's not mistake this. Judicial appointments do not solve the problem, they don't make it easier, it's not a silver bullet. That's very important to understand.

All this is doing is getting the courts organized in a way that will allow us to govern ourselves, and we have a lot of large decisions to make as our future-- in the future debates about our politics, but this is a very significant shift, and those who thought that the trends were all in the wrong direction and this was all over are wrong. This opens it up again I think, and--

HEWITT: That's it. And it's not losing.

SPALDING: --our country.

HEWITT: It's about not losing. It's about not losing. Matt Spalding, Director of the Kirby Center, thank you, my friend. I'm Spartacus!

SPARTACUS 1: I'm Spartacus!

SPARTACUS 2: I'm Spartacus!

HEWITT: We'll be back with all the Spartacuses in the Hugh Hewitt radio universe, including Generalissimo, Adam, Ben, all of you on the next Hugh Hewitt Show Monday, don't miss it.