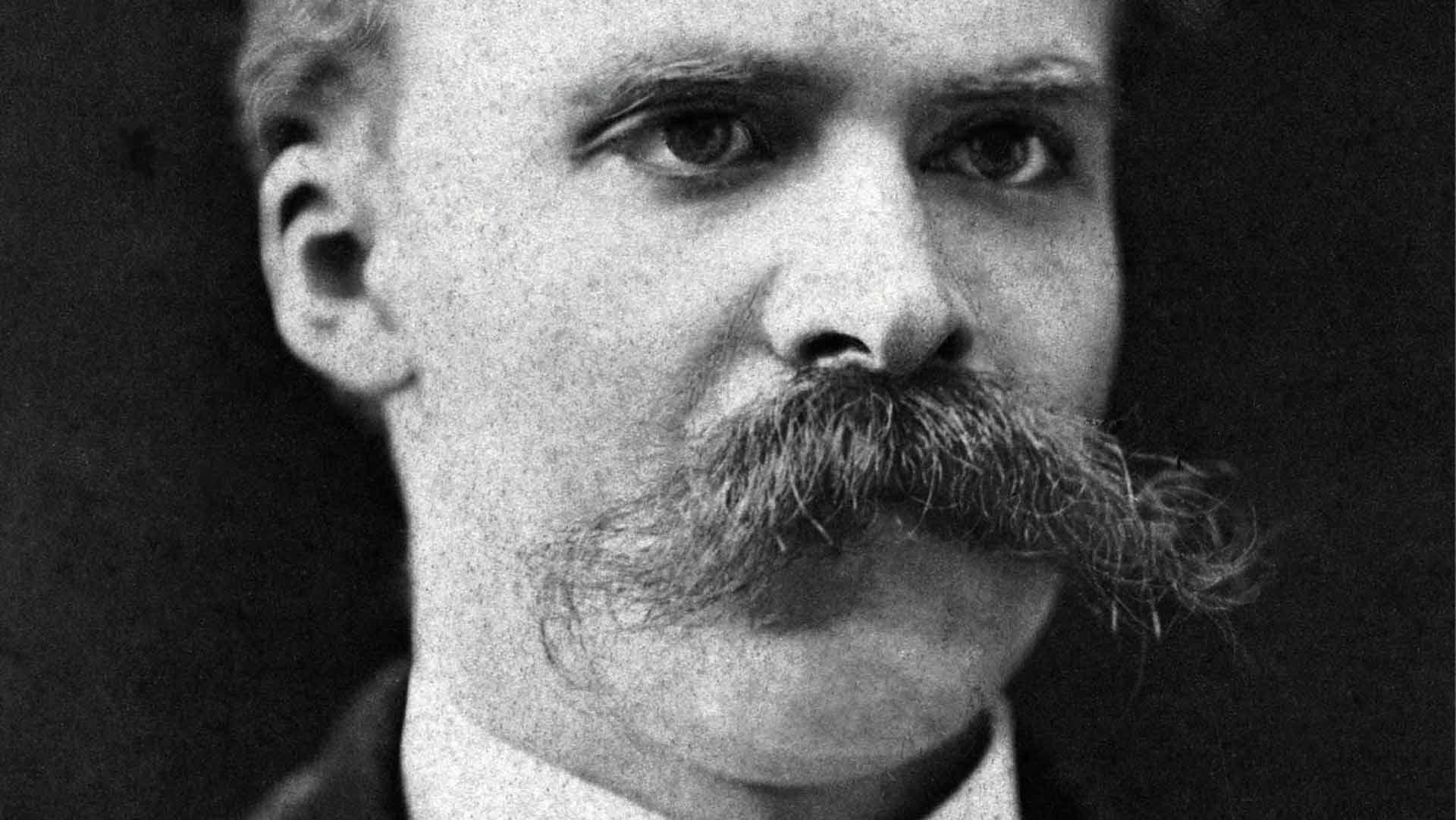

Nietzsche and His Lingering Impact

Share

By Hillsdale College Online Courses February 27, 2015

Dr. Arnn and Dr. Grant join Hugh Hewitt to discuss the impact of Nietzsche's philosophy.

Transcript:

HH: This is the last radio hour of the week. After I conclude this hour, the Hillsdale Dialogue, I’m jumping in the car and heading to LAX and flying to Washington, D.C. You can see me tomorrow on Meet the Press, and I’m looking forward to that on Sunday, I mean, on Meet the Press. But I’m joined in this Hillsdale Dialogue by Dr. Larry Arnn, the president of Hillsdale College and Dr. John Grant, his colleague on the faculty there. Dr. Grant was with us last week as the Hillsdale Dialogue, our weekly conversation about one of the great books or figures or ideas of the West turned to Hegel. And he helped us, along with Thomas West, get through an introduction to Hegel. But Dr. Arnn is back this week. Dr. Arnn, welcome, and did you have a good vacation?

LA: I was working.

HH: Okay.

LA: Yeah, yeah, I did, well, I heard you guys did a good job last week. And…

HH: I think you skipped Hegel because it’s so hard.

LA: No.

HH: I think you turned it over to West and to Grant and said you two handle this, because I don’t want to deal with Hegel.

LA: No, well, so ancient philosophy seems simple and turned out to complex. Modern philosophy seems complex and turns out to be simple.

HH: That’s very well said. So I did get a lot of reaction to that conversation, and John Grant, I don’t know if people have talked to you about that. Most people are more afraid to pick up Hegel than anything else, and they found it actually illuminating and inviting into his work.

JG: Oh, great.

HH: So that means we have to go to Nietzsche next. And so I’ll have you start, Dr. Arnn. Do you keep the students away from Nietzsche until well into their first year at least? Or do you throw them into Nietzsche early?

LA: Well, I’ve had a kid graduate here in recent years, a very smart, young man by the name of Kuiper, and I always called him Nietzsche Boy, because he was, I caught him when he was a freshman carrying around a book that John Grant has on the desk right now, The Portable Nietzsche. And no, we teach Nietzsche here. Nietzsche is a hoot. Nietzsche is great to study.

HH: Why do you say that?

LA: Well, I mean, first of all, he was literally insane.

HH: Yes.

LA: …at the end of his life. But Nietzsche is a poet who draws out the implications and results of modern philosophy. And he tries to overcome them by more modern philosophy. We are going to see if Grant agrees with all this. But I studied Nietzsche quite a lot in graduate school, and with a great teacher named Harry Neumann, who was a nihilist. And Nietzsche makes things wonderfully explicit. And he’s a poet. Nietzsche is beautiful.

HH: Everyone at some point in their college education should be carrying around Thus Spoke Zarathustra. But you just said a nihilist. And would you pause, Dr. Grant, and tell us what that means? Let’s define the term at the beginning.

JG: Well, the idea, and this relates to Nietzsche’s argument that God is dead. And what he menas by that is not just the God of the Bible, but any ideal that transcends becoming or history, is not, we found out that’s, there’s nothing to guide us but our will.

HH: And was he the first? Or was he merely a midpoint in the development of that, which is everywhere and apparent in many places, we’ll talk about its headline nature today. But where did it start?

JG: Well, there’s a complicated, scholarly argument this goes back to early modernity, or even pre-modernity with medieval nominalism, but I think that Nietzsche is the great, along the lines of what Dr. Arnn was just saying, Nietzsche’s the guy that really shows us the meaning of nihilism or the problem of nihilism, because now, that’s often celebrated, the idea that atheism or nihilism is a truth. And Nietzsche, he thought it was true, but he also thought it was horrifying, that the idea that life has no guidance, that we don’t, there’s no meaning that’s not created by man. Now he thought that also gave us an opportunity to make meaning, and perhaps make man better than he’d ever been before. But it is a terrible truth, and his books really explore that very nicely, that problem, better than anybody else I know.

HH: Now Dr. Arnn, when you look up and you see headlines like we’ve seen this week, three 15 and 16 year olds leaving London to go join ISIS, you see three jihadis in Brooklyn trying to join the Islamic State, you see the London guy who has been doing all the beheadings, do you think of nihilism? Or do you think of anti-nihilism, that they are too invested in sacred scripture and an understanding of the way the world works?

LA: Well, there’s two things going on there. One is these guys are busy remaking the world, right? This is like a huge crusade to create a utopia here on Earth. And that’s kind of modern philosophy. And then this reading of the Koran, you know, and the zeal for it, I don’t know what account to give of that, I know there’s a lot of Muslims that don’t do that, but there’s an awful lot who do. So it’s a mixture, I think, and this God, it’s not, you know, as He appears in these beheadings. That’s not a particularly holy thing to do.

HH: Now yesterday, actually two days ago, I had on former Florida Governor Jeb Bush. And I asked him what’s the tap root of this, and he mocked the idea that it was joblessness, as everyone mocked Marie Harf earlier in the week for saying it. But he did come back around to the idea of alienation and segregated cultures, and the feeling, I thought he was saying, nihilism. I didn’t have time to tease it out of him. I thought he was saying, because I was getting ready for Nietzsche, that he was saying that the reaction to that world is hyper-religiosity. Do you think there’s some merit to that?

LA: Well, let’s see what John thinks. One thing I think is look at the treatment of women. And what that means is people are practicing a kind of domestic despotism, and that’s part of a larger despotism. They live under commands that mean their life is in peril if they vary from the faith. But on the other hand, inside their home, they’re tyrannizing, the men, are tyrannizing everybody in it. And so it looks to me like it’s kind of a top to bottom and bottom to top phenomenon that’s going on.

HH: But the attraction, Dr. Grant, for young people adrift in this society, do you think there’s some credit to Governor Bush’s belief that the radical aloneness of this society makes for easily recruitable people to belong to something, even something as crazy as this?

JG: Well, yes, and I would say in a Nietzschean analysis, Nietzsche was, strangely enough, while a nihilist, he was pro-life in this way, and that he hated the anti-life character of modern civilization. And he, especially he talks about this in terms of concepts of the religion of pity, you know, having an orientation toward the world where you elevate failure as your standard. And I think young people, I think Nietzsche was right about that, that being a problem in his time and more so in ours. And young people rebel against that. They want nobility, struggle, they want goals. And if we don’t give them decent goals, if our civilization doesn’t give them decent goals, they’ll go after these false gods, to use the Biblical metaphor.

HH: I’ll come back to beyond good and evil in a second, but while we’re there, Dr. Grant, since you did Hegel last week with Dr. West and myself, how does Nietzsche come out of Hegel? What’s the relationship there?

JG: They both have the attitude that history is, and I don’t mean the study of history in the ordinary academic sense, but history rather than nature is the standard you should use to guide yourself. Except Hegel thought that that historical process is a rational process knowable by human reason that gives us guidance. And Nietzsche says well, it is the standard, but it doesn’t actually give us any clear guidance. And if we don’t make something of it, if we don’t will values to make life possible, history will kill us, you might say, or that belief in history will kill us.

HH: Now I don’t understand that. I don’t understand how anyone can come that. I can understand how Hegel comes to his conclusion that we’re marching forward towards the last man like we talked about last week, and it’s all, even if there’s a cycle to it and it breaks and you start over and you build up again, there’s a cycle to it. How do you come to there is a standard, but it’s irrational or not knowable?

JG: Nietzsche did, he’s got a nice book on this called The Advantage and Disadvantage of History For Life, and where he…

HH: I have never heard of that. Interesting.

JG: It’s his, in his untimely meditations, it’s his second untimely meditation, one of his earlier books. And he rejects the Hegelian orientation, because he doesn’t believe we’re, he looks around and he says how can we be at the peak of things when you still have all sorts of problems, you know, degradation, injustice. And he actually thinks we’ve been declining. One of Nietzsche’s other arguments is we’re not progressing. We’re declining. Man was greater, the Greeks were greater than we are today. And there’s something, you know, the practical point that Nietzsche used to make this is we can’t even punish criminals in our day, which is more real today than it was, of course, in the 1870s and ‘80s in Germany. We lack the strength of will to do that, the belief in our civilization that our way of life is good and should be protected against those. And you know, one sees this also in our foreign policy, and well, how do we confront evil, and should we, and can we label evil, evil, and things like that. And Nietzsche, he saw the roots of that and said how can be progressing when we think that?

LA: And Hegel, and in socialism, a development on Hegel, history is comfortable, right, because it’s going to go a certain way, and it’s going to work out for us.

HH: Yup.

LA: And it can’t help but do that, right? And we should pick that point up, because we’ll read Nietzsche’s description of that.

— – – —

HH: As we went to break, Dr.Arnn was saying for whom history is a comforter, a blanket, a wonderful, warming thing to have underneath your feet, all will work out. And you were about to say, Dr. Arnn, Nietzsche says none of that?

LA: So here’s Nietzsche’s description of the end of history. No shepherd and one herd. Everyone wants the same. Everyone is the same. Whoever feels different goes willingly into the madhouse. One has one’s little pleasures for the day, and one’s little pleasures for the night. But one has a regard for health. They like warmth, the members of this herd, and so they spend their time rubbing up against each other. So you see, he’s describing a subhuman existence where everything is taken care of. That’s the last man. And so he wants, there’s no shepherds, see, anymore. There’s no God. There’s no leader. There’s no standard. Especially, it’s not so much, if there’s no standard, then Nietzsche, in Zarathustra, especially, he argues that there has to be a man. There has to be the overman. And Zarathustra is his prophet. And he described what his overman will do. He will supply by will what we lack in nature, or God. And so Nietzsche is raging against this decline into comfort and lassitude.

HH: And that overman, of course, finds himself in mid-century in the person of Hitler. And is that the reason why so many people blame Nietzsche for the rise of the Nazis?

JG: I think that’s right, Hugh, and I don’t think that’s accurate. I mean, Nietzsche’s philosophy is very problematic for, and we’ve just seen an example of this, this contempt for modern man, which is useful in its way. It points to some problems, but it goes too far. Nietzsche, for instance, was appalled at German anti-Semitism, and thought this is just an absolutely idiotic view. And he talks about this in Chapter 8 of his book, Beyond Good And Evil.

HH: Well, if he is blamed, why is he then wrongly blamed for the Nazis?

JG: Well, for some good reason. This exultation of harshness, of toughness, this contempt for the weak and the suffering, there’s something to that, a very irresponsible way of talking, extravagant praise of cruelty, you know, he’s arguing against the idea that we need to get rid of all cruelty as this would be degrading to human beings anything tough. But he goes too far in that. So there’s something to that attitude that Tom West talked about this last week, the Nazi elevation of pain and struggle above all other things, not subordinated to any good. And Nietzsche contributed to that attitude.

HH: So Dr. Arnn, I’m curious given your mastery of all things Churchill. If Churchill is aware of this trend before it manifests itself in Hitler, is he aware of the philosophy growing of the nihilists?

LA: Oh, very much. It’s, the theme of Churchill’s life is that it’s summarized best in an essay called Mass Effects On Modern Life. And what he says is there are two things going on. One is we are gaining such power over nature that we lose our greatness. And that’s kind of a Nietzschean theme.

HH: Yeah.

LA: And the great crags sticking above us of granite that we can look up to, we don’t have them anymore .But that’s not the worst thing going on. The worst thing going on is as we gain power over nature, we lose standards. That’s a Nietzschean theme. And so Churchill’s argument is what’s going to happen is we’re going to start controlling ourselves. That means some of us are going to control others of us…

HH: Overmans.

LA: A few over all of us, and Churchill says, and this is where he parts from Nietzsche. He says two things, and they’re very profound. One of them is he says imagine a society 16 generations hence where we can live as long as want, we can go anywhere interplanetary we want, and we can have pleasures unimagined to us today. What is the good of all that, he says, because he says there will still be these questions remaining, and they are what we here, why are we here, who are we, who do we serve. And the failure to address those questions leads to an ache in our souls that will never make us happy with tyranny. And then in another place, he says it is urgent that moral philosophy hold its ground against these evolutionary tendencies. It would be better to make no material progress than to extinguish ourselves by this progress.

HH: Oh, how interesting. So he is aware and fighting the philosophical battle at the same time he is fighting the actual battle of regimes.

LA: It’s simply, Hugh, amazing how he did that. And I can’t account for it. I just marvel at it.

HH: So Dr. Grant, was there a reaction in philosophical circles to the rise of this crazy poet? And we mentioned he goes mad. How long was he mad for? Was it intermittent?

JG: Well, towards the end of his writing career, he went mad and pretty much stayed mad, was institutionalized until he died, about a decade, ten or eleven years.

HH: Okay, so was there a push back contemporaneous with his writing?

JH: Initially, there was very little reaction to Nietzsche’s writing. A lot of it was, we would say self-published, you know, would be the thing now, and in a few hundred copies. And I think Nietzsche became very powerful after World War I when the European faith in progress was shattered. So you might say Hegel reined through World War, up until World War I, and philosophically, and that experience of tremendous upheaval, loss of life and barbarism, that made people look to Nietzsche.

HH: On any raft that comes out of a river, there’s always, you know, a current on which it’s being led, and it starts from somewhere. So how did Nietzsche, if he’s in the madhouse by 1900, who moves his works mainstream, because lots of people self-publish stuff that never goes anywhere. Who picked him up and ran with the ball?

JG: I think Nietzsche’s great student was Martin Heidegger, and who’s not simply a Nietzschean, but he took Nietzsche up. And the combination of Nietzsche and Heidegger dominates today still what is typically called postmodern thought.

HH: And did anyone say to Heidegger no on where you’re heading, and where you’re taking Nietzsche is going to end in the ruin of all?

LA: Leo Strauss. Yeah, well, you have to, about Nietzsche, I’ll just add a point. And I’m forgetting their names right now and I apologize, but there were four or five guys who were loyal to Nietzsche who went and picked him up when he, Nietzsche spent the last 15 years of life, well, the last 7 or 8 years before he got sick, in I think about 1890, he was off around the world – staying in Paris, staying in Italy. And he went nuts, and they came and got him. And then they collected his manuscripts. And they caused, like Beyond Good And Evil, they caused that to be published. And I think they printed a hundred copies.

HH: Hold onto that thought.

— – – – –

HH: Dr. Arnn, you were saying when we went to break, four or five guys would come and collect Nietzsche whenever he broke down, and they caused to have published his Beyond Good And Evil, and I guess Zarathustra. Would it have mattered if they had not done so? Would we be in an appreciably different place had they not picked him up and collected the books?

LA: Well, some of the things might have been lost, but you also have to know Nietzsche rubbed shoulders with the great and the near-great during his life. He was a prodigy. He was the youngest person ever to be a tenured professor in a Germany university, a Prussian university. And you know, he knew Richard Wagner very well. And see, that’s one reason why there’s a kind of a joke about Hitler, because you know, Wagner wrote this great, powerful, sometimes turgid, heroic music. And Nietzsche decided he was a lightweight.

HH: I didn’t know that.

LA: Well, Hitler was a bore. So I mean, there are great descriptions of what it was like to be around Hitler.

HH: Right.

LA: And it was all pretentious, and like the dinner conversation was just deadly boring. And this guy, Albert Speer, who was a…

HH: Architect.

LA: …architect and a powerful guy, a very learned guy, he wrote a good book describing what all that was like. And they were all talking about, they were all pretending that everything they said was profound. You think Nietzsche would have put up with that?

HH: As opposed to Churchill’s dining table where everything was funny and deep and profound.

LA: Yeah, that’s it.

HH: But it was also wild. So Dr. Grant, let’s get to the heart of it. People who are listening expect us to talk about God being dead. And they expect us, why do they expect that from us?

JG: Sorry…

HH: In the context of a conversation about Nietzsche, they expect us to talk about God being dead.

JG: Oh, this is one of Nietzsche’s famous assertions which he repeats several times. And I mentioned earlier, what he means by that is we’ve discovered, the embrace of rationalism in the Western world, beginning with Socrates and carrying down through modern science has caused us to become very honest in our investigations. And then we’ve discovered there is no God. And by that, he also means there’s no nature, there’s no permanent standards. It’s not just God isn’t the Biblical God or something like that. And we’ve investigated that to death, you might say. And now we have to live with this knowledge that there is no, nothing guiding us except our own wills. And we’ll either go the way of the last man, in degradation, or the way of the overman, which could be the peak of humanity if it’s done according to Nietzsche’s prescription.

HH: So you put in your notes to me, you know, the question was he a teacher of evil. I’ve always assumed the answer is yes, but you put a question mark behind that.

JG: Yeah, I think in some ways, Nietzsche’s a teacher of evil, and I mentioned his irresponsibility and his praise of cruelty. I think his argument that God is dead to be another example of that irresponsibility. Nietzsche has a great diagnosis of the problem in the Western soul, though, and I think especially in his discussion of the religion of pity and its attack on everything that’s strong or noble, the idea that we have to elevate everything that is suffering, that doesn’t succeed, not just take care of it but elevate it. That’s life defeating for our civilization.

HH: Now okay, so square the circle, Dr. Arnn. That sounds a lot like Christianity. Was he anti-Christian not in terms of sort of a Salafist hatred of Christianity, but anti the teachings of Christ?

LA: Nietzsche said that Christ was Plato for the masses. And he was very critical of Christianity as the religion of pity, as John mentioned earlier And what pity means is you worship the weakest. And that means you compromise society and its strength. And also, when you pity, it’s depressing, he says. It’s not exhilarating. And you focus on the lowest. And what you need to do is you need to struggle, and you need to take charge, and you need to place yourself under stress so that you can rise to heroism. And that’s sort of a shallow way of putting what the overman does. He does something more. Nietzsche believes that the great, horrific truth is that everything happens over and over again the same way, the eternal return of the same. And that can become a good if you will it. And that’s the will to power.

— – – – –

HH: And Dr. Arnn, I said at the break there are two people appearing at the, he’s leaving, but Churchill’s coming onto the stage, and the 20th Century is really a battle, isn’t it, between good and evil and whether or not life has meaning and can be infused with Christian understanding or not?

LA: Well, Churchill’s faith and conviction is that life does have meaning, and that the human soul cannot be satisfied except by addressing that meaning. And that’s Churchill’s ultimate defense. He says in Mass Effects In Modern Life, he says that the Russian Bolsheviks have taken these mass effects to their utmost perfection, and they have built a society that is exactly like the society of the white ant. Not the bee, because it can make no honey. And then that’s the gloomy paragraph. And then immediately following, he says but human nature is more intractable than ant nature. It is it wants the glory and the safeguard of mankind that it is easy to lead and hard to drive. So we’re not beings made, we’re like every kind of being, by the way. It has, we have our good. We have our essence. And our essence is that we can address ourselves to the right thing, which is something outside our will.

HH: So the question becomes, and I’ll ask this of Dr. Grant. Why teach young people, why lead them to the fountainhead of nihilism? Why do that?

JG: Well, I think a serious liberal education should plumb all these fundamental questions, and that’s one of the things we’re trying to do at the college. And it would be, I think, irresponsible if we did not provide them with alternatives, which is the pursuit of truth in the defense of liberty we do here.

LA: So let me supplement that. So Professor Jaffa and Professor Neumann, a nihilist, and a great teacher of Nietzsche, would teach courses together sometimes. And it was the Harry and Harry show. They were both named Harry. And here’s what would emerge very often. Harry Neumann would day that Harry Jaffa is the alternative to Nietzsche, because what Nietzsche does is display the actual effects of modern philosophy. And we’re going to have those effects. We’re going to have the last man probably more likely than the overman unless you listen to Harry Jaffa and the resurrection of nature and right and God. And so they would talk like that. And then Professor Jaffa would say sometimes, and Neumann would say Professor Jaffa, who did in the last month, he’d say Professor Jaffa is raising an army. And then Professor Jaffa would say and Harry Neumann is coming along behind to shoot the stragglers.

HH: But Harry Neumann, tell me about someone who spends their life admiring and studying Nietzsche.

LA: I don’t know about admiring, and there’s deep, but I will tell you what he could do, just so people can get a sense of what a, because you know, by the way, one of the things you have to do, one of the things Churchill said the human soul needs to do is to understand. That’s what Grant just said. What are the implications of these great teachings that have had a big effect? Nietzsche helps to make them explicit. But what Harry Neumann could do, I took his course on Nietzsche, and then I audited it twice more.

HH: Wow.

LA: And you learned to buy the editions of the books of all of Nietzsche’s books that he had, because when somebody would ask him a question, he would name a book and a page number. And when everybody found it, he would tell you which paragraph on the page to read, and you would read your answer. And then he would explain it. He was a master. And Professor Jaffa’s reading of Harry Neumann was that Harry Neumann was in fact a man whose father and grandfather fought for the German Army, and that he felt the loss of the conviction that moved them. They were Jews, but they were Germans, too. And he thought that that loss of faith and conviction afflicted Harry Neumann. And now Harry Neumann never said this, by the way. And he said that Professor Nuemann’s bent to make all this explicit was actually sort of life Nietzsche, an attempt at some kind of a recovery.

HH: How interesting. And Dr. Grant, we’ve got two minutes here, if you are a true Nietzschean follower, would he say, would that student say he had a hope for civilization, that he had an end game that was other than despair and the overman?

JG: Well, he did have a hope. It’s, you might say brutal hope. It’s a hope in greatness that in the future, people will rise. The Overman, this is the overman, who will be able to overcome nihilism by willing, willing values that will be conducive to greatness and strength. But it’s the nastiness of it is that means something like tyranny. He was never very specific about what that meant. But it’s nasty. So it’s optimism, it’s optimistic, but it’s a very strange kind of optimism.

HH: Isn’t that Pol Pot, Larry Arnn? Isn’t that, I’m not, I don’t know what that is. Who is that?

LA: Well, you also have to remember that Nietzsche was, I think this is true, impatient with every practical thing he ever saw. So he wouldn’t have liked Pol Pot. He didn’t like anybody.

HH: So in the last minute, Dr. Grant, how do you recommend people go about reading Nietzsche? What order?

JG: I would, I mean, he has a very large corpus, and people will talk about different phases in his thought. I think the most accessible of his books is Beyond Good And Evil, which is also a comprehensive book. And there’s a nice translation of it by Walter Kaufmann.

HH: And Dr. Arnn, you agree with that?

LA: Yeah, oh yeah.

HH: And what’s the next one? When do they pick up Zarathustra?

LA: Well, that’s, it’s better, in my little opinion, to, it’s good to have a teacher. But Zarathustra is kind of a poetic work, right?

HH: Right.

LA: And I’m told by people who read German well that it’s beautiful, and it’s also impressionistic. And so you’ve got to get some, like I read a passage from the prologue to the Zarathustra earlier…

HH: Yes.

LA: …about the last man. It’s written like that. And it’s fun once you get the hang of it.

HH: Dr. Larry Arnn, Dr. John Grant, the Hillsdale Dialogue, thanks to you both.