The Importance of First Freedoms

Share

By Hillsdale College Online Courses February 27, 2017

Dr. Paul Rahe offers a sobering reminder of the real purpose behind the First Amendment. In combination, the “first freedoms” (i.e., freedom of religion, speech, press, petition, and assembly) provide the people with everything they need to maintain control of the government. Without them, there are no checks in place to prevent incumbents from legislating themselves into permanent positions of power.

The following video is a clip from Hillsdale’s Online Course: “Public Policy from a Constitutional Viewpoint,” featuring Paul A. Rahe, the Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Professor in the Western Heritage, and John J. Miller, director of the Dow Journalism Program.

Transcript:

John J. Miller:

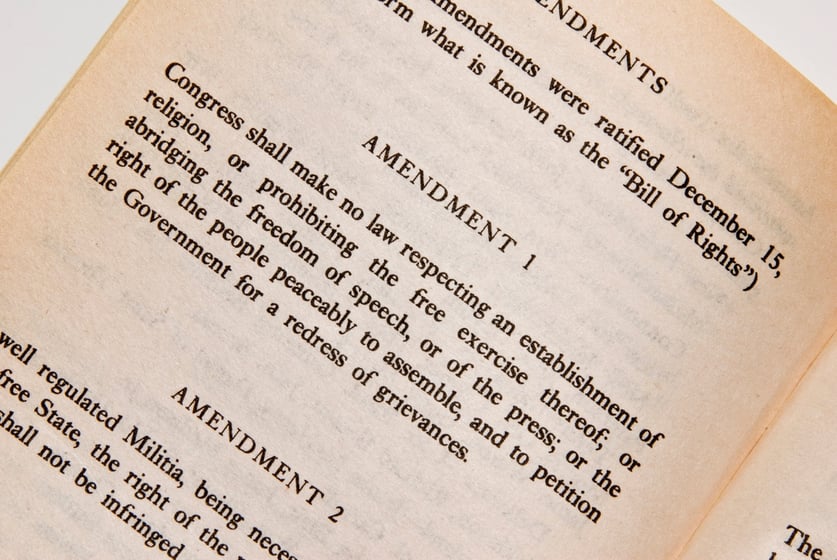

Sometimes when we talk about the First Amendment, we refer to the first freedom, which is commonly called freedom of religion, or the first freedoms, all five: religion, speech, press, petition, assembly. But the word first is important here. These are the first freedoms of the First Amendment. They have a kind of pride of place, don't they?

Paul Moreno:

Of course they have a pride of place, because they are fundamental to the very character of our regime. To begin with, we are a republic. If you don't have freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom to congregate, freedom to petition, you don't have any freedom at all. You have masters. You don't have people who serve you. These freedoms are essential to having free elections, because if we can't talk about it and argue about it and make our case, and the other side can't talk about it and argue about it and make their case, then what are we doing? The answer is: we are genuflecting to our masters.

The other side, of course, is freedom of religion. Modern liberalism, liberal democracy, is built upon freedom of religion, on taking religious disputes out of the public sphere and making them private matters, and it is the ground that allows Catholics and Protestants and Jews and Muslims and Hindus to live alongside one another in peace. We agree to disagree, and we take certain things out of the public sphere.

There are sort of two sides to the character of our political regime. One of them is limited government, and it's limited because it doesn't have anything to say about religion, and there are implications of that, of course. The other side is it's a republic, which is to say we choose the people who will act on our behalf. We can cashier them, and we do so with great regularity. But if you eliminate freedom of speech, freedom of the press, if you eliminate the freedom to congregate, the freedom to petition, the freedom to make noise, then you've eliminated free elections, and there are a lot of people who would love to eliminate free elections. In fact, almost every politician is tempted—maybe they don't always give way to the temptation—to eliminate free elections, because they surely do not want to risk not being reelected themselves.

John Miller:

You mean incumbents, obviously?

Paul Rahe:

Yes. The people out of office really do have an interest in freedom of speech and freedom of the press and so forth, but incumbents, the people who make the laws, don't. What does the amendment say? Congress shall make no laws. It says that because you don't want to put the fox in control of the hen house. You know what you will get if Congress makes laws [concerning those freedoms]. Those laws will be made to protect incumbents.